The Collection

A vast majority of the objects in the house today belonged to the Glessner family. Discover more about the collections at Glessner House through the stories of the artists and designers who created the objects which the Glessners owned and cherished. Descendants of John and Frances Glessner have generously donated these items to the house, where they continue to be cared for in their original setting, providing an authentic experience for our visitors.

TO SEARCH THIS COLUMN

Press Ctrl/Command + f on your keyboard and type in your search term in the window that will pop up. It’s an easy way to search for a specific item or topic!

Object of the Month

May 2024 - Library mantel made by Isaac Scott

Isaac Scott (1845-1920) was a close friend of the Glessners and designed countless items for their homes including picture frames, furniture, decorative objects, and embroideries. This mantel was made for the Glessners’ library in their previous home, located at the northeast corner of Washington and Morgan streets. It was installed in March 1877, just 18 months after the Glessners met Scott and commissioned their first pieces from him.

The walnut mantel is a tour-de-force of carving and design, and shows not only Scott’s considerable abilities, but his familiarity with design trends of the time including the work of British designer Charles Eastlake and the German-born American designer Daniel Pabst. The mantel, which replaced a typical incised marble fireplace surround of the era, also functioned to showcase the Glessners’ growing collection of decorative arts, with tall compartments to either side of the firebox, and two shallow compartments directly above.

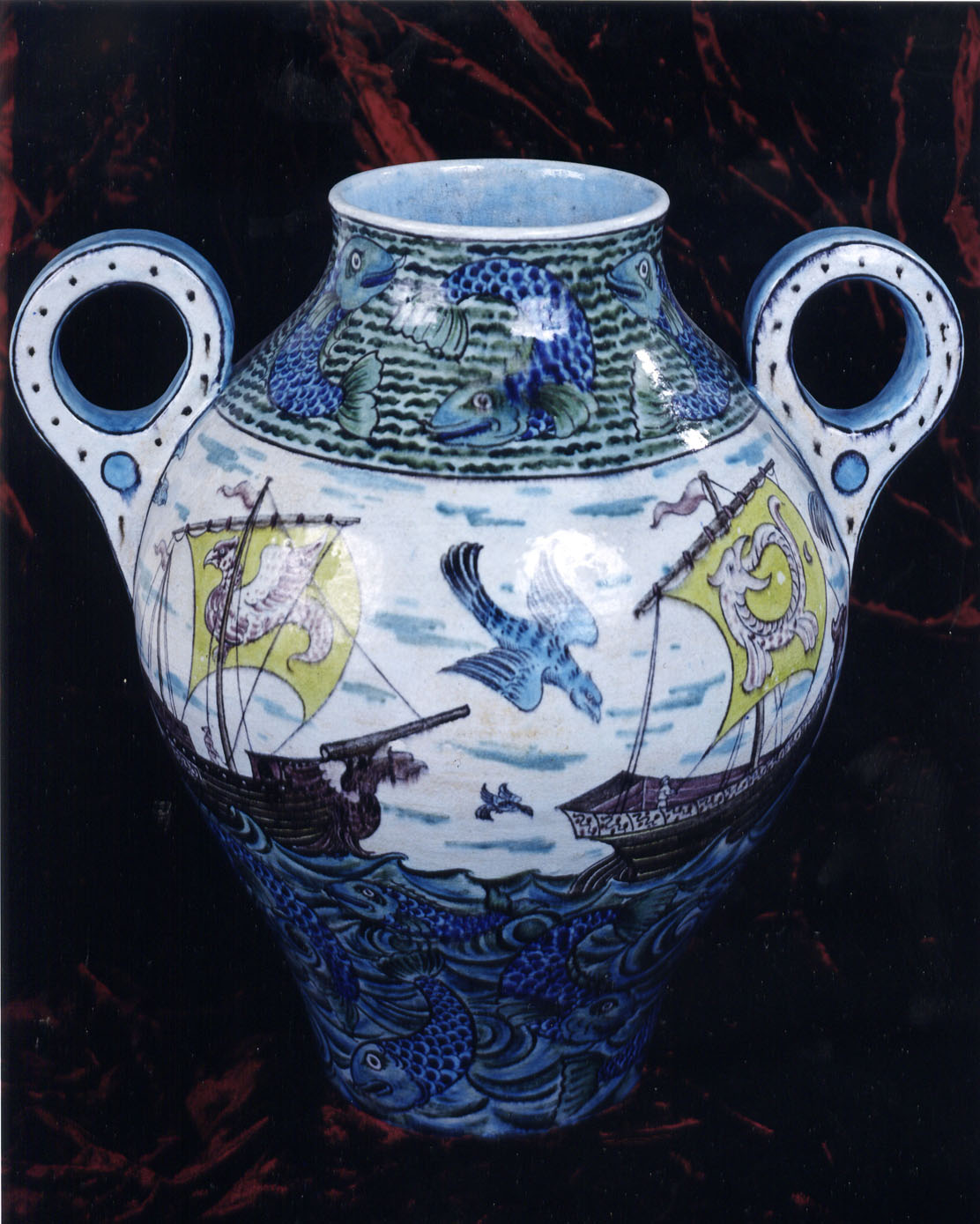

Many of the objects visible in the historic photograph (lower image above) remain in the collection today, including the pair of Japanese vases, the two large round Pilgrim bottle vases (also by Scott), and framed tiles painted by Frances Glessner’s sister, Helen Macbeth. Five tiles attributed to the British painter Henry Holiday, depicting the story of Lancelot and Elaine as told in Idylls of the King by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, were set directly above the firebox, and are now displayed on the plate rail in the main hall.

The top of the mantel is framed in billet molding consisting of small, elongated cylinders. The front edge of the mantel shelf has a repeating pattern of leaves and buds, possibly depicting geraniums. The shelf is supported on four brackets, with alternating designs of highly conventionalized flowers and leaves, and pairs of squat spindles set in between. Above the firebox, a diamond fret molding is divided into five sections capped with shallow segmental arches, to complement the five tiles that were originally installed below. The paneled compartments to either side of the firebox, set beneath additional segmental arches, feature saw tooth trim, turnings, reeding, and more conventionalized flowers. Several of the details relate to other pieces Scott made for the library, including two bookcases, a writing desk, and a table.

When the Glessners moved to their new Prairie Avenue home in December 1887, they brought this mantel with them (as well as a second mantel Scott made for their bedroom), as they knew the Washington Street house was to be demolished for construction of a coffin factory. The next summer, the mantels were shipped to their summer estate, The Rocks, in New Hampshire, and this mantel (with a modified firebox) was installed in the sitting room of their home, known simply as the Big House.

By the mid-1940s, the Big House had come into possession of their grandson, John Jacob Glessner II, who had it razed in 1946. Prior to that, the contents of the house were auctioned off, and the Glessners’ daughter, Frances Glessner Lee, acquired a number of pieces including the two Scott-designed mantels. She never installed them in her home, but safely stored them in a building at The Rocks, near her own cottage.

In 1968, her daughter, Martha Lee Batchelder, made the first of many large donations of objects to Glessner House. That first donation, consisting of more than 140 items, included dozens of items by Isaac Scott, including the two mantels. Today, they are displayed in George’s bedroom. The mantels could have easily been lost at various points in their history, so we are grateful that three generations of the Glessner family cared for them over nine decades, so that visitors today can continue to appreciate Scott’s remarkable artistry.

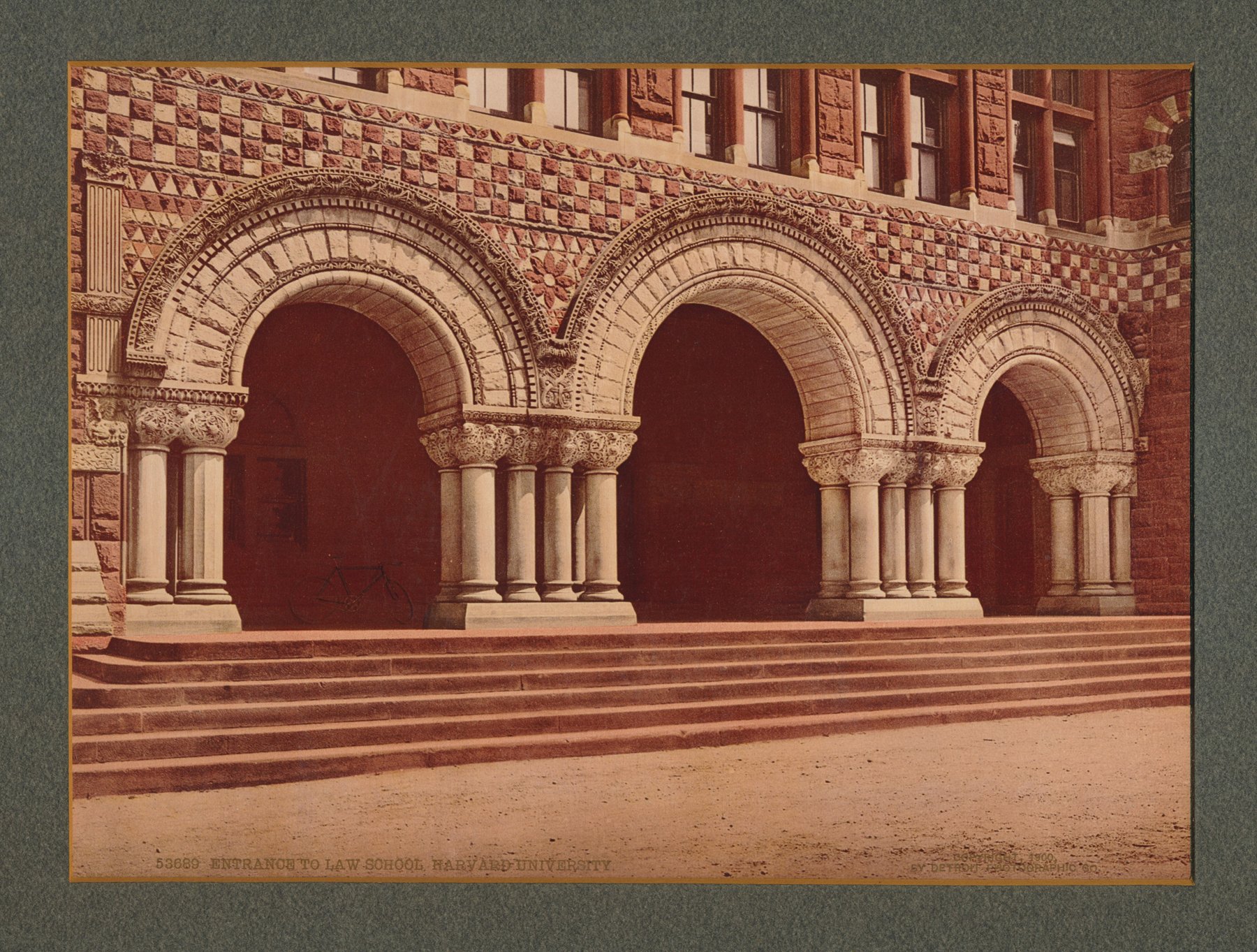

April 2024 - Photochrom print of Austin Hall

This photograph shows the main entrance into Austin Hall, completed in 1884 to house the Law School at Harvard University. The Glessners displayed the photo in the cork alcove adjacent to their library, beside a large engraving of Boston’s Trinity Church, and a portrait of Henry Hobson Richardson, the architect of both buildings (and Glessner House). It appears to have been one of the Glessner’s favorite buildings by Richardson, as they also owned a large portfolio of photographs of Austin Hall, issued in 1886 as part of the Monographs of American Architecture series published by The American Architect and Building News. By coincidence, when their son George moved into his suite of three rooms in the Hastings residence hall at Harvard in 1891, Austin Hall would have been the view directly outside his windows.

In 1879, Edward Austin, who made his fortune in railroads, approached the president of Harvard about funding a building on the campus, even though he had never attended. President Charles W. Eliot (one of the Glessners’ closest friends) discussed the need for a larger building for the law school. Although Austin noted that he “detested lawyers,” he provided more than $140,000 to construct the building in memory of his older brother, Samuel.

Henry Hobson Richardson received the commission for the building in February 1881, having designed the nearby Sever Hall for Harvard three years earlier. Whereas Sever, with its all brick exterior, was meant to blend in with the existing buildings at Harvard Yard, Austin Hall was a more typical expression of Richardson’s work at the time, being composed entirely of stone. The overall plan was T-shape, with a two-story central block containing a large lecture room with reading room above, and one-story wings to either side, each with an additional lecture room.

As seen in the photograph, the front façade is dominated by a series of three massive Romanesque arches composed of Ohio sandstone. An elaborate carving program included the column capitals, featuring a variety of real and mythological creatures. To the left of the arches, Richardson included a stone with his monogram, set amidst his architect’s tools and other symbols displaying his reliance on “Golden Section” proportioning. A broad horizontal band of alternating light and dark blocks of Longmeadow sandstone sits above the arches, emphasizing the overall horizontal feel of the building. The back side of the building is an entirely different composition, and is anchored by the large central block. Early Richardson biographer Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer regarded this elevation as one of Richardson’s most beautiful designs.

The interior is richly decorated as well. The most elaborate space is the soaring reading room on the second floor, featuring exposed tie beams carved with the heads of dragons and wild boars, and secured with decorative iron strapwork. The room also features a massive fireplace composed of stone and brick, with a carved panel in memory of Samuel Austin.

The Glessner’s photograph was copyrighted in 1900 by the Detroit Photographic Company, founded in the late 1890s to produce color postcards and prints. The company secured the rights to a special printing process known as Photochrom, developed by Hans Jakob Schmid of Orell Fussli & Co. in Switzerland. Also known as the Aäc process, it involved hand painting black and white negatives to create color lithographic printing plates, with each color requiring a separate plate. The back of the mount is stamped “Aäc Photograph – We Photograph the World in the Colors of Nature – Detroit Photographic Company: Scenic and Art Publishers, Detroit, Michigan.” A label from the retailer indicates that the Glessners acquired the photograph in the shop of G. J. Esselen, located on Bromfield Street in Boston.

The building remains in use by the Law School.

Click here to be redirected to our jigsaw puzzle featuring this image.

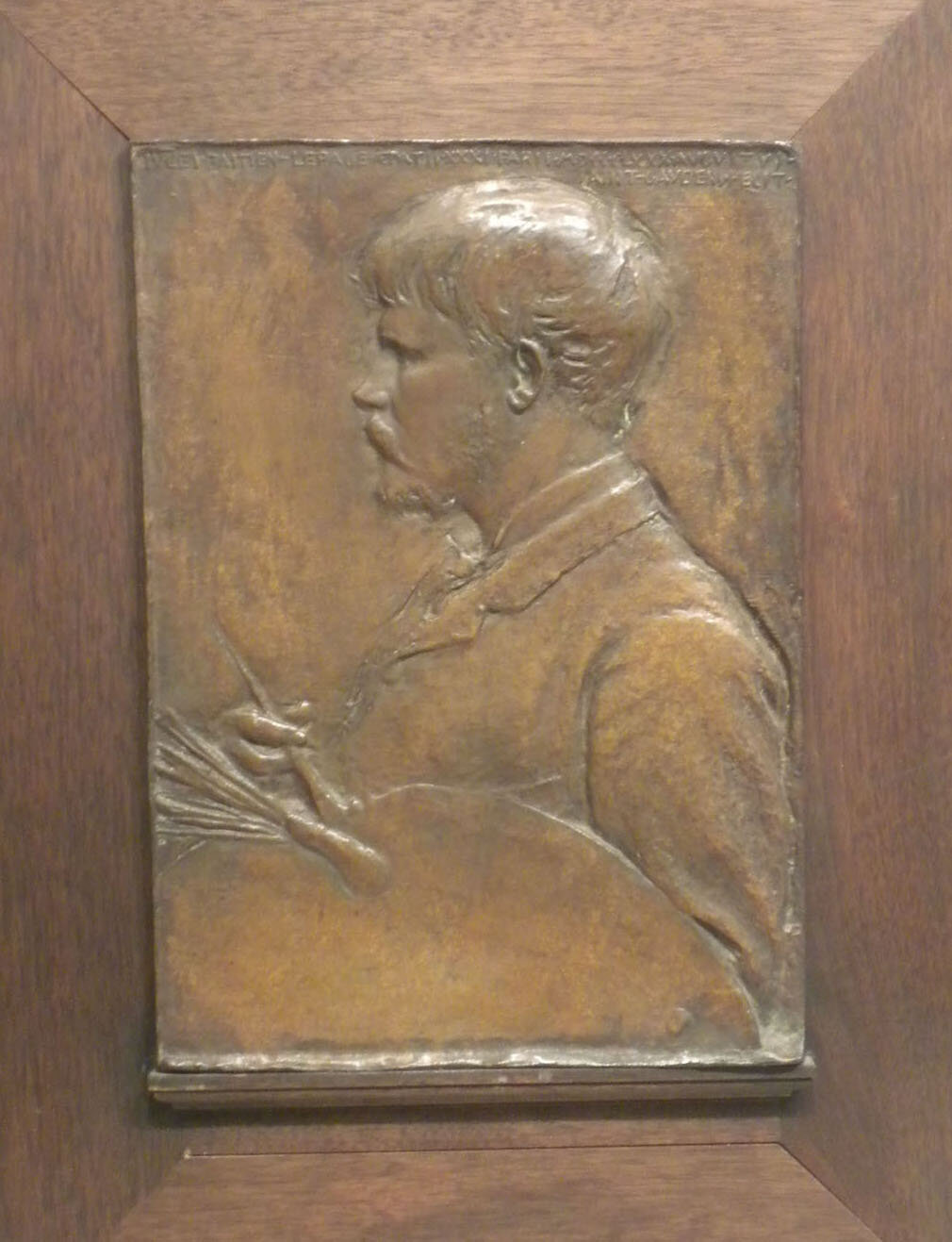

March 2024 - Portrait of Francis Beidler

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Chicago lumberman and philanthropist Francis Beidler. Shown above is an engraving of Beidler taken from volume 5 of the six volume Industrial Chicago, published in 1894 by the Goodspeed Publishing Company of Chicago. Volume 5, “The Lumber Interests,” was written by George W. Hotchkiss, a prominent journalist who came to Chicago in 1877 and wrote extensively on the lumber trade, until taking over as editor of the Evanston Press in 1892.

Francis Beidler was born in Chicago in 1854, his father Jacob being one of the most successful lumbermen in the city. He was raised in the family home at the northeast corner of Washington and Morgan streets on the near west side. In 1874, that home was sold to John and Frances Glessner, and they remained there until moving to Prairie Avenue in December 1887.

Beidler went to work for his father at the age of 16, and in 1874 helped form the South Branch Lumber Company of which he served as secretary; in later years it was reorganized as Francis Beidler & Co. With Benjamin F. Ferguson, he co-founded the Santee River Cypress Lumber Company in 1881, acquiring 165,000 acres of land in central South Carolina. (Over 18,000 acres survive today as the Francis Beidler Forest, an Audubon wildlife sanctuary and the largest virgin stand of cypress-tupelo forest in the world). He also operated lumber firms in New York and North Dakota. Having earned the respect of those in the industry, he was appointed the first president of the Lumberman’s Association when it was formed in the 1880s.

Beidler died on March 4, 1924, in his home at 4736 S. Drexel Blvd. The provisions of his will reflected the growing trend in Chicago at the time for wealthy businessmen to establish charitable foundations to continue their philanthropic work. The estate was estimated at $3 million (the equivalent of more than $50 million today). More than half of the estate was set aside to establish the Francis Beidler Foundation for charitable and patriotic purposes. An interesting provision funded flags for every classroom at the Jacob Beidler School, 3151 W. Walnut Street, named for his father. Additionally, each student, upon graduation, would be provided with copies of both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

His widow, Elizabeth, received the family home and an annual annuity. Their two children, Francis, Jr. and Elizabeth, each received $500,000 with this request:

“It is my wish that my son will incline to scientific study, statesmanship or political pursuits. It also is my wish that my daughter will be inclined to spend much of her time in charitable pursuits. In furtherance of this desire of mine, I have amply provided for my children. I wish them to work in furthering the interests of their country rather than for the accumulation of more money.”

The Foundation remains active today, and Glessner House is fortunate to have been a beneficiary of Beidler’s generosity. In 1974, the Foundation funded the buildout of the second floor Beidler Conference Room, created from the former conservatory and adjacent walk-in closets. Ongoing grants, provided annually over the past 50 years, are used for the maintenance and refreshing of the room as needed. This year, funds are being used to upgrade the lighting, replace the carpeting, repair and refinish the adjacent hallway floor, and install a 65” monitor for use during meetings.

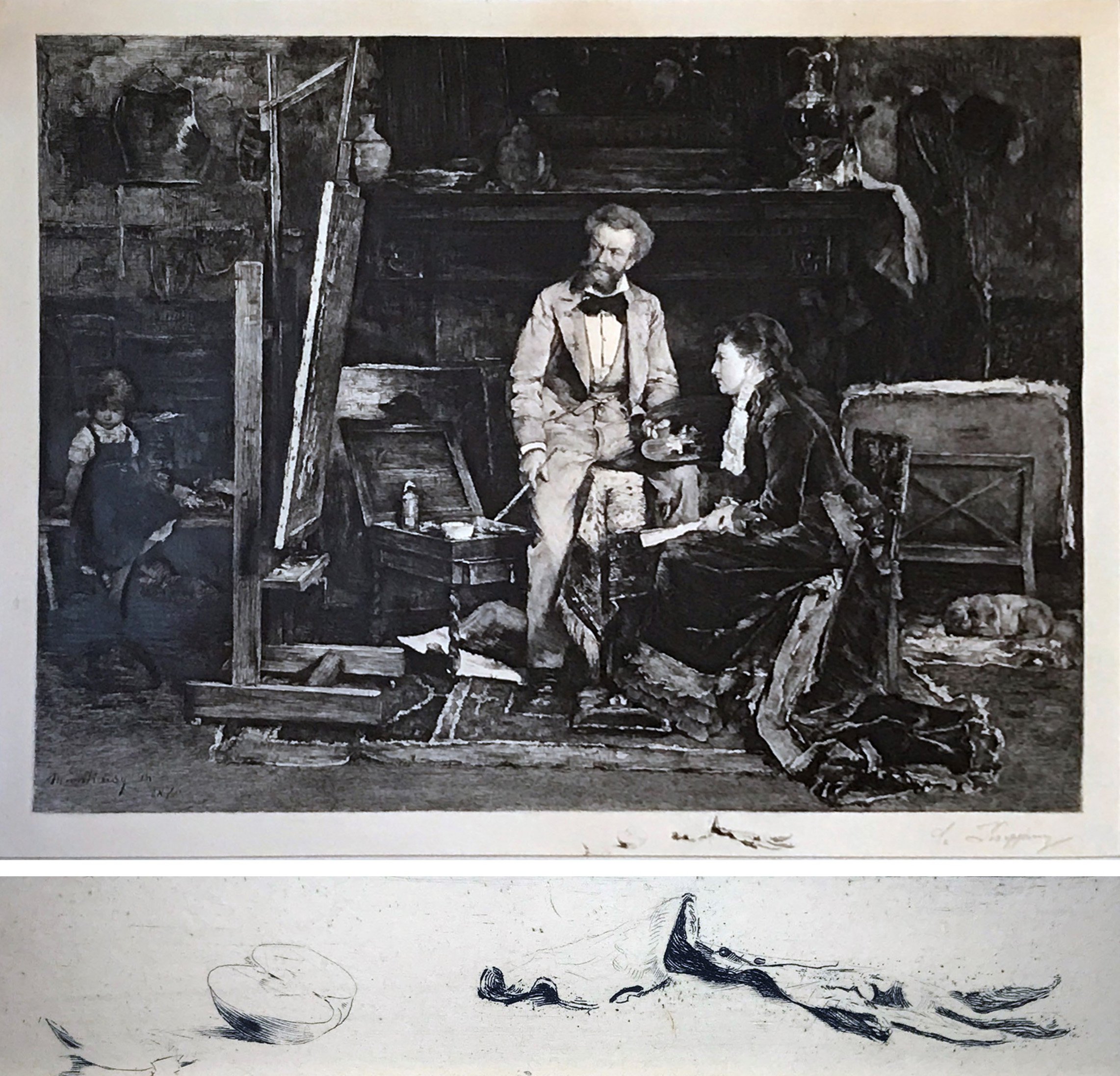

February 2024 - “In the Studio” etching

The Glessners were avid collectors of etchings and steel engravings, and many of the pieces are still exhibited in the house today. “In the Studio” would have had special meaning for the couple, as they visited the Paris studio depicted. The visit was recorded in a journal entry by John Glessner dated February 28, 1890:

“We went to call on Munkacsy at his studio. The ceiling of this was very high. On the stairway going up was a magnificent bust of Munkacsy by Barrias. The reception room was furnished with screens and sofas and hangings, had a bright fire burning and was filled with French callers. Mr. M. called his wife, who speaks English, but she was at the other end of the room and did not reach us. He took us into his studio, through a door draped with 3 or 4 thicknesses of hangings, and we sat there on a corner sofa awhile talking with him through Miss Scharff. He regretted not speaking English as we did our lack of French. He had no work done and apparently little in progress. The studio had a stuffed horse in it and some stuffs and was very light.”

Mihály Munkácsy was one of Hungary’s most revered and important late 19th century painters, who earned an international reputation for his genre pictures and large-scale Biblical paintings. He was born Mihály Leó Lieb in 1844 in Munkács, Hungary, then part of the Austrian Empire, and now the Ukrainian city of Mukachevo. His mother died when he was an infant and his father was killed when he was four, during the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. The young boy was raised by an uncle who supported his growing interest in art. In 1868, he changed his last name to honor the place of his birth.

Munkácsy achieved widespread recognition in 1869 for his painting, “The Last Day of a Condemned Man,” which was awarded the Gold Medal at the Paris Salon the next year. He moved permanently to Paris in 1872 and befriended the Baron and Baronesse De Marches. The Baron died in 1873, and a year later, Munkácsy married his widow, which opened the door to the Parisian upper classes, and provided the financial resources to establish a luxurious studio and pursue his artistic endeavors.

In 1876, he completed a large oil painting, “In the Studio,” upon which our engraving is based. (The original is now in the collection of the Hungarian National Gallery). The artist is standing at center, and his wife Cécile, who also acted as his manager, is examining the painting on his easel. The identity of the young child standing at far left is unknown as neither of them had any children. The two central figures are positioned in front of a tall fireplace, with abundant ornaments all around – the very same setting where the Glessners sat and talked with the artist, through Miss Violette Scharff, Fanny’s paid companion, who spoke fluent English and French.

The painting was made into an etching by 1884, when it appeared in the July 12 issue of Harper’s Weekly. The etcher was Karl Köpping/Koepping (1848-1914), a native of Dresden who trained as a painter and printmaker, and later taught etching at the Berlin Academy. Koepping’s original pencil signature appears below the lower right hand corner of the Glessners’ copy. To the left of his signature, he added an ink remarque – a small original bit of artwork. It depicts half of an apple and a crumpled woman’s evening glove. An enlarged view of the remarque is shown at the bottom of the image above.

Munkácsy enjoyed a successful career. Among his better known works are “The Blind Milton Dictating ‘Paradise Lost’ to his Daughters” (now in the collection of the New York Public Library), “Hungarian Conquest” for the House of Parliament in Budapest, and “Glorification of the Renaissance,” a ceiling fresco for the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. His health declined in the mid-1890s, and he died in a mental hospital in Bonn, Germany in 1900.

It is not known exactly when the Glessners acquired their etching, but it was no doubt purchased as a remembrance of their 1890 meeting with Munkácsy in his studio. They had the etching set into a simple oak frame with a gold wash and hung it in the parlor guestroom.

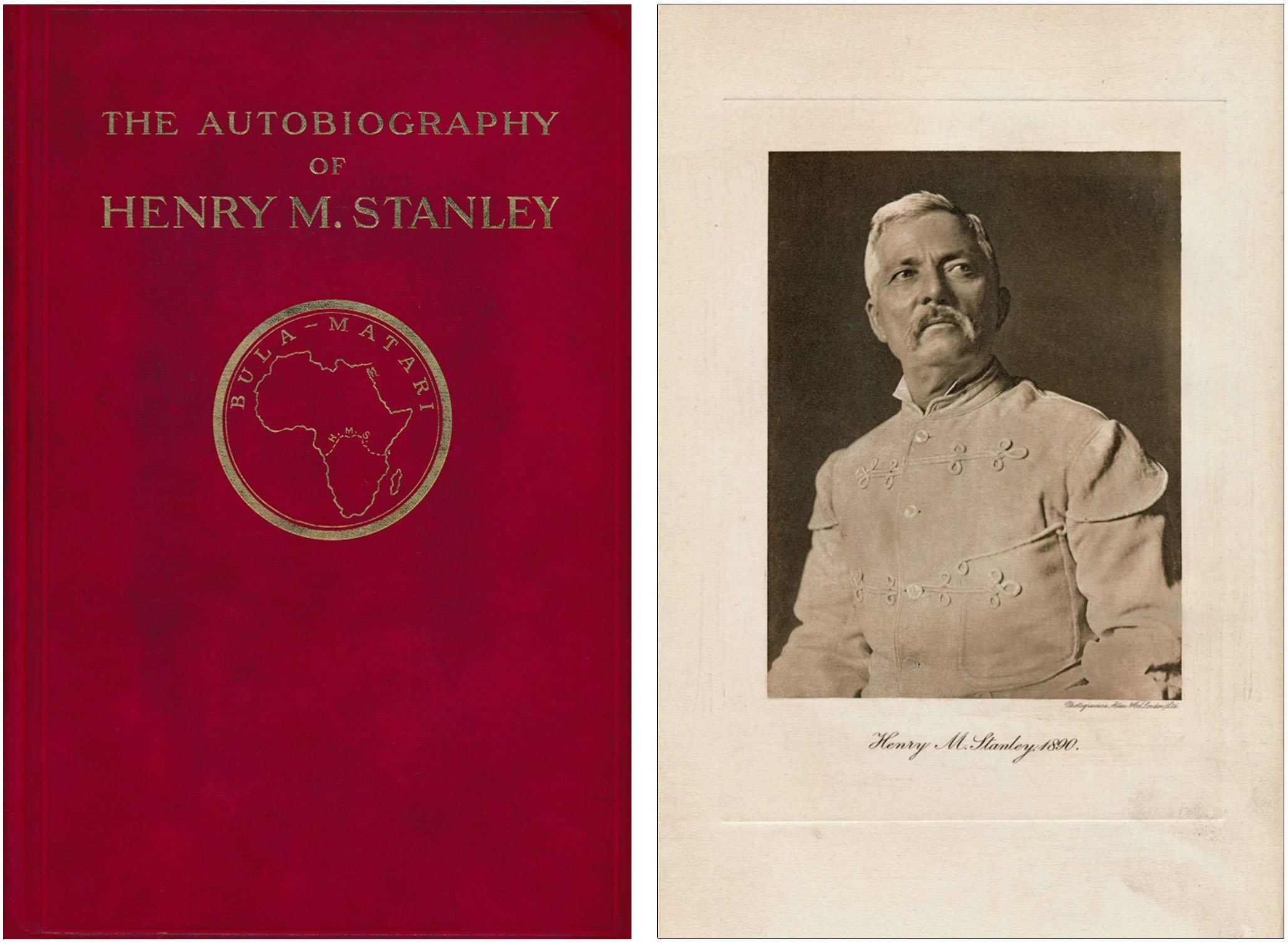

January 2024 - The Autobiography of Henry M. Stanley

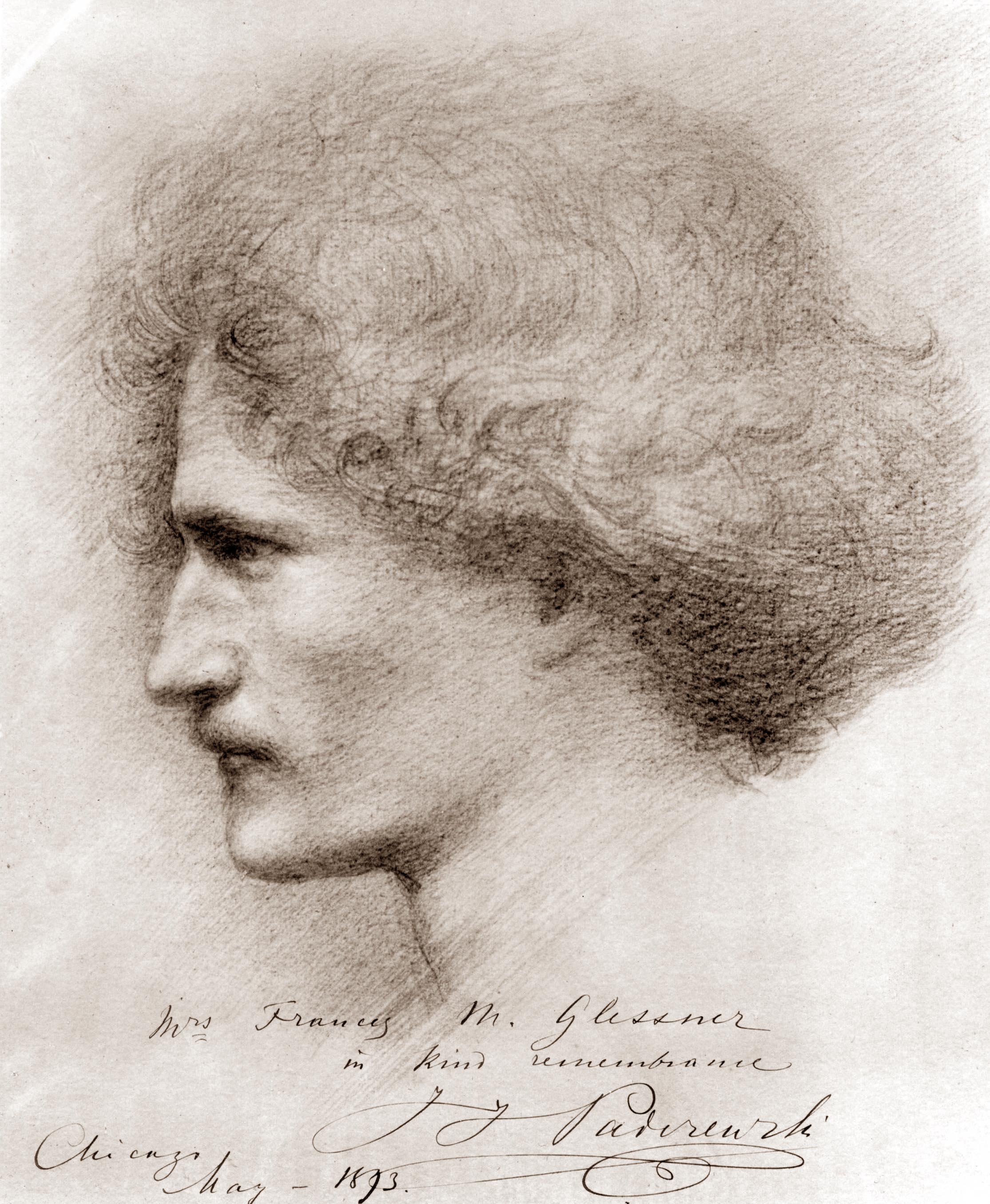

On January 1, 1891, Frances Glessner recorded in her journal that she and her husband attended a reception at the home of Franklin and Emily MacVeagh, 1400 N. Lake Shore Drive, given in honor of the famous explorer, Henry M. Stanley (shown above in 1890). Although she noted “Mr. Stanley was a disappointment,” she found his wife, the English artist Dorothy Tennant Stanley, “pleasant and bright.”

The Glessner library contains three volumes written by Stanley: the two volume Through the Dark Continent published in 1878, and The Autobiography of Henry M. Stanley published posthumously in 1909. Each volume of Through the Dark Continent features half-leather binding, with marbled covers, endsheets, and edges. A pocket on the inside back cover of each volume contains a large fold-out map of the regions Stanley explored. He coined the term “dark continent” in the book, a reference to the portions of the African jungle that were so dense that almost no sunlight made it to the ground. The volumes recount his 999-day journey from 1874 to 1877, financed by the New York Herald and the Daily Telegraph, to explore and document the lakes and rivers in central Africa, and to locate the source of the Nile River. Stanley also explored the Lualaba, which had been renamed in honor of Dr. David Livingstone, who started mapping the river prior to his death in 1873. Now known as the Congo River, Stanley traced it all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Autobiography of Henry M. Stanley contains the autobiography as left unfinished when he died in May 1904. It was carefully edited by his wife Dorothy, who wrote the preface to defend her husband’s honor. She wrote, in part:

“The ungenerous conduct displayed toward Stanley by a portion of the Press and Public would have been truly extraordinary, but for the historical treatment of Columbus and other great explorers into the Unknown. Stanley was not only violently attacked on his return from every expedition, but it was, for instance, insinuated that he had not discovered Livingstone, while some even dared to denounce, as forgeries, the autograph letters brought home from Livingstone to his children, notwithstanding their own assurance to the contrary. The reception produced, therefore, a bitter disappointment, only to be appreciated by the reader when he has completed this survey of Stanley’s splendid personality.”

The volume is covered in red buckram, with the title stamped in gold. Below the title, a central medallion features the outline of Africa with the words BULA-MATARI above. This phrase, which translates as “breaker of rocks,” was given to Stanley during his travels; he later requested that it be inscribed on his headstone. A detailed fold-out map of Central Africa, personally supervised by Stanley, is found inside the back cover.

Stanley achieved international fame in 1871 when he was engaged by the New York Herald to lead an expedition into central Africa to locate the missionary and explorer Dr. David Livingstone, who had not been heard from in several years. When he finally found him on November 10, 1871, Stanley was said to have greeted the doctor with the famous phrase, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?,” although most scholars today agree the words were not spoken at the time, but were fabricated in later accounts of the mission.

Stanley made several more trips to Africa, his last from 1887 to 1889 focusing on the relief of Emin Pasha, the Egyptian governor of Equatoria (now part of modern-day South Sudan). It was this last expedition that served as the focus of his lecture tour in the United States, which brought him to Chicago for two lectures at the Auditorium theater on January 2 and 3, 1891. The newspapers covered every aspect of his visit in detail, from his arrival at the Auditorium hotel on January 1, to the various receptions and entertainments held in his honor, and the content of his talks. He left Chicago on January 5 to lecture in Milwaukee.

Today there is considerable controversy regarding Stanley’s legacy, ranging from his treatment of Africans to his role in the colonization of the continent by European nations including Belgium, for which he helped establish the Congo Free State. The surviving volumes in the Glessner library are a reminder of the fascination he held for many in the last decades of the 19th century, most of whom would only learn about Africa through his writings.

December 2023 - Silver tête-à-tête set by Dominick & Haff

This charming sterling silver coffee service was a wedding gift to Frances Glessner and Blewett Lee in February 1898. The gift came from William Laughlin Glessner, an uncle of Frances, and a younger brother of her father. William was a highly successful steel manufacturer in Wheeling, West Virginia, serving as president of the Laughlin Nail Company, and becoming vice president of the Whitaker-Glessner Company in 1902, when it was formed through merger with the Whitaker Iron Company.

The three-piece set is an example of a cabaret service, a term used to denote a small tea or coffee set. More specifically, it is known as a tête-à-tête set, as the one pint coffeepot is designed to provide service for two. That term, French for head-to-head, normally refers to a private conversation between two people.

The coffeepot is designed in a butternut squash form. The handle is woven in rattan to make it comfortable to hold, as the heat of the coffee would transfer into the silver handle. The creamer and open sugar bowl are both squat in form, the unusual and exotic shape a subtle reference to Turkish design. All three pieces feature gently curving tendrils extending from the handles and spouts, a typical motif of the Art Nouveau movement. The date stamp on the bottom indicates it was made in 1889, making this a very early example of Art Nouveau. Americans were introduced to the style around that time through French posters and magazine covers designed by the Paris-based Swiss graphic designer Eugene Grasset and others.

The set was made by Dominick & Haff, a leading American silver manufacturer based in New York. Their work is generally considered to be on par with that of Tiffany and Gorham. The firm was established in 1872 by Henry B. Dominick (1847-1928) and Leroy B. Haff (1841-1893), and was formally incorporated in 1889, the year this service was made. Examples of their wares, which often feature cutting-edge design, can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cooper Hewitt. The Art Institute of Chicago possesses a stunning Egyptian Revival centerpiece made about 1880.

Dominick & Haff’s silver was retailed through the finest jewelers and luxury goods purveyors in the United States including Bailey, Banks and Biddle, and C. D. Peacock; the latter is where this set was purchased. Elijah Peacock, an immigrant from Cambridge, England, started the business in Chicago as The House of Peacock in February 1837, one month before the city was incorporated.

In 1889 his son Charles Daniel Peacock took control and changed the name to C. D. Peacock. The establishment was located at the northeast corner of State and Adams in 1898 when this set was purchased. It is best remembered for its long-time location which opened in the Palmer House hotel in June 1927. The store featured three sets of brass peacock doors designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany; the doors remain, although Peacock no longer has a store at this location. C. D. Peacock does maintain three locations in the Chicago suburbs, making it the oldest continually operating business in the Chicagoland area.

The coffee service was passed down through Frances Glessner Lee’s son and eldest grandson and was donated to Glessner House earlier this year.

November 2023 - Half-model of Vought SB2U Vindicator

This month’s object honors John Glessner Lee, the Glessners’ first grandchild, who was born 125 years ago, December 5, 1898. Lee had a distinguished career as an aeronautical engineer, being awarded numerous patents, and serving as a consultant to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). During his tenure as a project engineer with the Stout Metal Airplane Division of Ford Motor Company in the mid-1920s, he was one of six men who designed the well-known Ford tri-motor plane. Moving on to the Fairchild Airplane and Motor Company, he helped to develop the type of plane used by Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd on his missions to Antarctica. In 1932, Lee was hired by United Aircraft as a project engineer, eventually rising to the position of director of the research department. He retired in 1964.

It was during his time working in the Chance-Vought Division of United Aircraft that he designed the Navy Scout dive-bomber shown in this half-model, which Lee constructed in the early 1940s. The half-model is constructed of wood and is set into a frame which measures 18-1/2 by 24 inches. The tip of the airplane wing projects a full two inches off the surface. The plane is painted black and silver and is mounted to a wood board painted sky blue. Half-models are commonly made for ships and boats and are often known as half-hull models. Lee’s model is a rare example of an airplane and is different in another important way. Half-hull models are always shown in profile where you see one side of the ship or boat. This provided all the information needed for the ship builder, since the vessels are completely symmetrical. The model shown here depicts the airplane in three-quarter view.

The back side of the piece features a detailed note from Lee, written in 1974 on his home stationery – Old Mountain Road, Farmington, Connecticut. It reads:

“This is a half-model of the Vought SB2U-1 Navy Scout Dive-bomber. I was the principal designer and project engineer on this series of airplanes which carried a pilot and a bomber-gunner and were powered by a Pratt & Whitney 1535 engine of around 800 hp. They were replaced by more powerful types just before World War II. They were used by the Americans, the British, the French, and the Argentines, and a few were flown by the Germans who captured them from the French. A couple saw active service in the defense of Midway Island against the Japanese. I made this model myself about 1942-45. John G. Lee, Dec. 11, 1974”

A second note on the reverse cautioned the possessor not to hold the piece by the wing or it will split, and was written by “Daddy’s Brother,” a fictional character Lee developed. His antics and adventures were recorded on a regular basis in the family newsletter, The Lee News, which Lee wrote for decades.

The SB2U-1 was the first monoplane designed by Vought and was the first monoplane used by the Navy, replacing biplanes on carriers. The body was constructed of a truss design covered in fabric, except for the edges of the wings and the engine cowl which were made of metal. The prototype used a 700hp engine, which was replaced by an 825 hp engine when the model was put into production. The plane featured a forward firing Browning .30-caliber machine gun and a second machine gun in the rear cockpit, mounted to a flexible ring mount. The bomb load could carry a single 1,000 pound bomb or two 500 pound bombs. The first planes were delivered on December 13, 1937, and were placed on the U.S.S. Saratoga.

An upgraded version of the plane, designated the SB2U-3, did see service in the Battle of Midway, which took place June 4-7, 1942. By the end of that year, the remaining SB2Us were sent to various training units in the United States, having been replaced for active service by more powerful planes.

The only surviving example of an SB2U was recovered from Lake Michigan in 1990. It was last flown on June 21, 1943, during a training session conducted by the Naval Air Station at Glenview, Illinois. The plane failed to land properly on the training aircraft carrier Wolverine, hit the deck, and rolled off the starboard bow, sinking to the bottom of Lake Michigan; the pilot was unharmed. The salvaged plane required 20,000 hours of restoration work before being put on exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida in 1999.

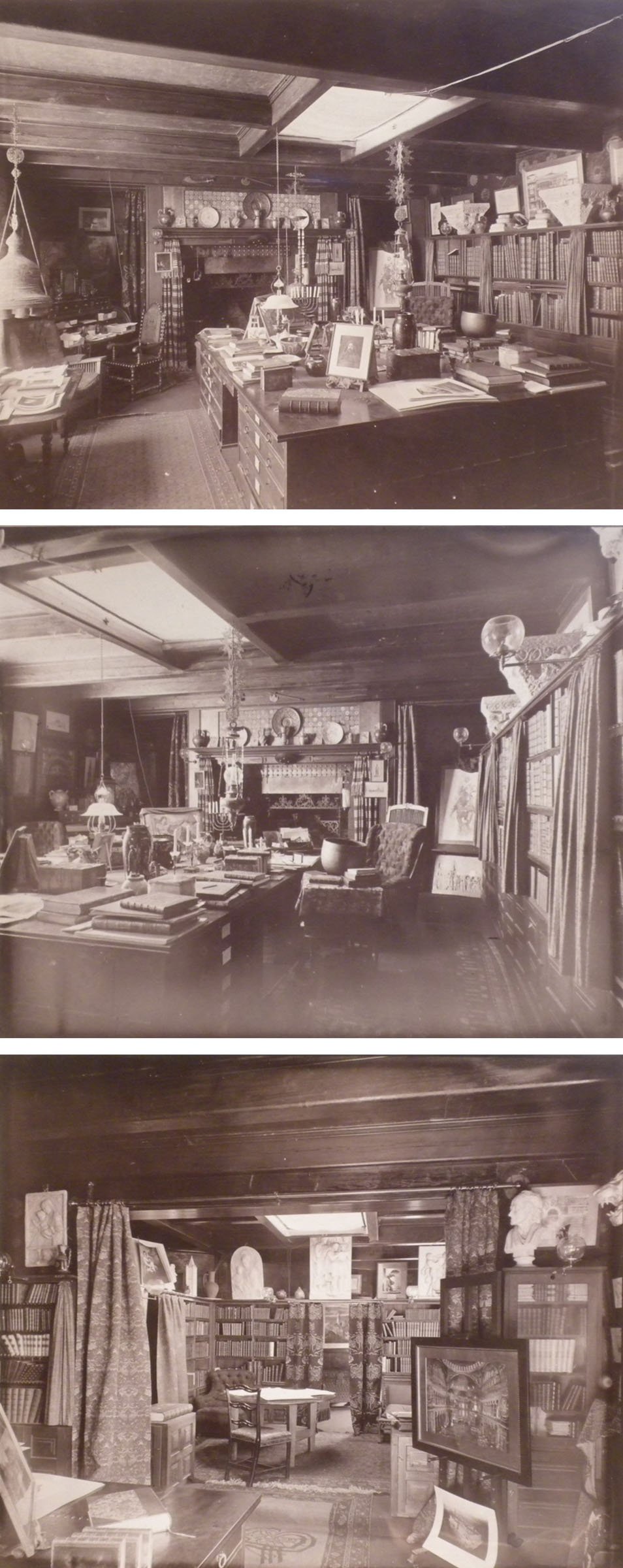

October 2023 - Three photographs of H. H. Richardson’s office/library

In honor of the 185th anniversary of the birth of architect Henry Hobson Richardson (born on September 29, 1838 in Louisiana), we showcase three photographs of the office/library in his Brookline, Massachusetts home, which he presented to the Glessners in 1885. They were both taken by the beautiful space upon their first visit to Richardson’s home in September of that year, and would have been grateful to have the photographs as a reminder of the room.

In an unpublished manuscription about Richardson that John Glessner prepared in 1914, he wrote:

“Mr. Richardson had his home and office in Brookline, just out of Boston. His private office was a large and beautiful room, with just enough disorder always to be pleasing, with stacks of fine books, with rare and beautiful objects scattered over shelves and tables, a great fireplace in one end before which, with back against a large table, was a deep and most comfortable lounge or couch. This was designed in his office especially for him - he was an exceedingly large man - and this generous sort of couch has since come to be know by the trade name of Davenport because A. H. Davenport was the maker.

“In this large room was the largest table I ever saw - 12’ square - so long and so wide that the maid could dust it only by getting on and sweeping the top with a broom. With the exception of a band of mahogany all round it 18” wide, it was covered with carpeting on which were most lovely articles of vertu, some magnificent great books, and the useful implements of his trade. At the farther end of this room, where the floor was one step higher than the rest, was a sheltered alcove, making a little room by itself.

“The room had an open timbered ceiling of hard pine and plaster. The span was long and the timbers correspondingly heavy, consequently there came some rather broad season checks even before the room was finished. Richardson found workmen on ladders puttying up the check splits. “The way I yanked them down from there,” he said, “was a caution.” “God Almighty made those checks,” he said. “Don’t you dare to fill them up.” And they didn’t dare."

“This is the room I liked the best. The walls were lined with deep shelves holding flat large (quartos and folios) architectural works, drawings and sketches. Small alcoves were on either side of the fireplace, filled with all manner of interesting things. A small wood fire was always laid in the great fireplace, burning whenever the weather would permit.”

The room was quite new at the time the Glessners visited. Richardson made several additions to his office wing through the years, and his office/library was part of an 1884 expansion that included an adjacent exhibition room. The room measured 25’ x 30’ and was the only part of the wing that was fireproof, being constructed of brick. The alcove referenced above (and seen in the bottom photograph) was originally an open verandah, and had been enclosed in 1885.

The design of Richardson’s office is reflected in Glessner House. Many elements of the room can be seen in the Glessners’ library, including the massive center desk, mid-height bookcases, beamed ceiling, and the sofa facing the fireplace at the end of the desk. The goldleaf ceiling appears in the Glessners’ dining room, and they selected the same Morris & Co. “Peacock and Dragon” portieres for their main hall that can be seen sheltering the alcoves to either side of Richardson’s fireplace.

The office wing, including Richardson’s office/library, was taken down a few years after he died, but the beauty of the space is forever preserved in these photographs and the written descriptions by the Glessners and others who were fortunate enough to experience the room in person.

September 2023 - Pair of lapis lazuli caskets

Glessner House is fortunate to possess two beautifully crafted lapis lazuli caskets that were most likely gifts from John Glessner’s business partner, Benjamin H. Warder. In July 1884, Frances Glessner noted in her journal that Warder had just returned from a nine month trip to Europe, and “he brought us a very beautiful little casket made of lapis lazuli.” Although different in size, the overall form of the two caskets is so similar that it seems very likely they were acquired together.

The term “casket” originally referred to a small box, typically used to store jewelry or other precious items. The word is derived from the French word cassette which means a small case. It was much later that the term casket became synonymous with coffin.

The gilt metalwork on the boxes would suggest they were made in Italy. Each features a beveled cover and a paneled body, raised on four lapis ball feet. The larger box measures 3-1/2 inches in length; the smaller 2-1/4 inches.

Lapis lazuli is a semi-precious stone known for its intense blue color. The metamorphic rock has been mined for more than 9,000 years in the northeast part of Afghanistan, which remain the major source for the stone. There are also large mines in Russia and Chile, and smaller mines in several other countries including the United States. Lapis is the Latin word for stone, and lazulum, based on the Persian word lajevard, means sky or heaven, so the name means “stone of the sky” or “stone of heaven.” The stone was used for the inlaid decoration on the funerary mask of Tutankhamun. During the Middle Ages, lapis was exported to Europe where it was ground into a powder and made into ultramarine, a paint more valuable than gold. Among the artists who used it was Vermeer, and it can be seen in the headwrap of his iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Benjamin H. Warder (1824-1894) was the senior member of the firm of Warder, Bushnell & Glessner, and was almost like a father figure to John Glessner, who was just 20 years old when he started with the firm in 1863. Warder retired from the firm in 1886, the same year he commissioned H. H. Richardson to design a home for him in Washington, D.C. (the rebuilt facade still stands). He died in Cairo, Egypt in 1894 while on vacation and his body was returned to the United States. Interment took place at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. in a specially commissioned 3,500 pound bronze (above-ground) sarcophagus. It was made by the Gorham Manufacturing Company from a design by the French-American sculptor Philip Martiny in collaboration with architects Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge.

The larger of the two caskets is displayed on the partners desk in the library; the smaller casket is located on the desk in the corner guestroom.

August 2023 - Glass plate negative of Hero Glessner

In honor of National Dog Month, we celebrate Hero Glessner, the smallest member of the family. The Skye Terrier was acquired by the Glessners in 1885 and died in 1892.

The Scottish dog breed originated on the Isle of Skye, the largest and northernmost island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The breed is known for being intelligent, strong-willed, loyal, and a good hunter. In 1840, Queen Victoria began keeping Skye Terriers, both the drop-eared and prick-eared varieties.

An image of Skye Terriers was included in The Illustrated Book of the Dog by Vero Shaw in 1881, and this led to its great popularity and introduction to the United States. An illustration also accompanied the story “Puff and the Baby,” found in Book of Cats and Dogs, and Other Friends, for Little Folks by James Johonnot, published in 1884. Fanny Glessner received a copy of that book (which remains in the library today) less than a year before Hero became part of the family.

The Skye Terrier was recognized as a breed by the American Kennel Club in 1887 (two years AFTER the Glessners acquired Hero; they always seemed to be on the cutting edge of things). It is now among the least known of the terrier breeds and is considered endangered.

George Glessner acquired Hero as he traveled to The Rocks with Isaac Scott in July 1885. He wrote to his mother:

“Hero does not know us yet and when we walk around or knock at the door, he barks or growls. He killed four woodchucks since we came and is now having some fun with a great big blow fly on the window.”

Frances Glessner arrived at The Rocks soon after and wrote:

“The dog needs a whole book to himself – he is so intelligent. He goes on tip toe when on the scent of a woodchuck. He snapped at a chicken when he first came up – and now (since Mr. Scott talked to him about it) he will lie in a coop full of young ones and let them nestle up to him. . . We have given him the blue velvet cushion.”

For Christmas that year, sixteen stockings were hung on the fireplace, and Hero’s contained a new collar with his name and George’s, along with a turkey bone tied up with a bow. Miss Violette Scharff, Fanny’s paid companion, was especially close to Hero, referring to him as her “angel.” She took primary responsibility for his care after George headed off to Harvard in the fall of 1890.

A scary incident took place in November 1891. Frances Glessner and Miss Scharff returned home from the opera late in the evening and were surprised when Hero did not come down to meet them. The house was searched, but he was nowhere to be found. The local watchman was notified, who in turn called the police. The next morning, the coachman, Charles Nelson, and his son Norman, went out early looking for Hero. They met up with a neighboring coachman who reported he heard Hero in the alley about 3:00am and brought him inside. Hero had apparently slipped out the back gate undetected late the night before and had roamed the alley for hours before being found. The coachman received a $5.00 reward (about $167 today).

Miss Scharff asked to take Hero with her when she sailed for Switzerland to visit her family in late April 1892. In a letter sent to Frances Glessner, she noted:

“Hero seems quite at home. Monday evening at supper, we had a large cake, ordered by my sister, on which could be read ‘Hail the conquering Hero comes.’ He is a conquering Hero, every one in town is admiring him.”

Two months later, the Glessners received word of Hero’s final days:

“Thanks to Madame Borel’s influence, all formalities were fulfilled, papers signed and I was allowed to have the little dog put out of pain here in the garden. I gave out after carrying Hero down and fled to my room. Daisy waited in the hall, when all was over, she wrapped the body in a cloth, put it in the basket, Mme. Borel sent her carriage for it and I will be shown the grave. I miss Hero more than words can tell. I expect every minute to find him again, but I feel I have done him the greatest kindness. He did not exactly suffer but for the last week or so was perfectly listless, slept all the time in corners, would only eat when fed by hand, did not want to be petted, and only showed any sign of life and pleasure when out walking. I am glad it is over but oh! I do want him so!”

The image above comes from a glass plate negative taken by George Glessner, one of hundreds he made over the years, in both 4x5 and 8x10 sizes. It shows Hero posed in the conservatory of the house in late 1888.

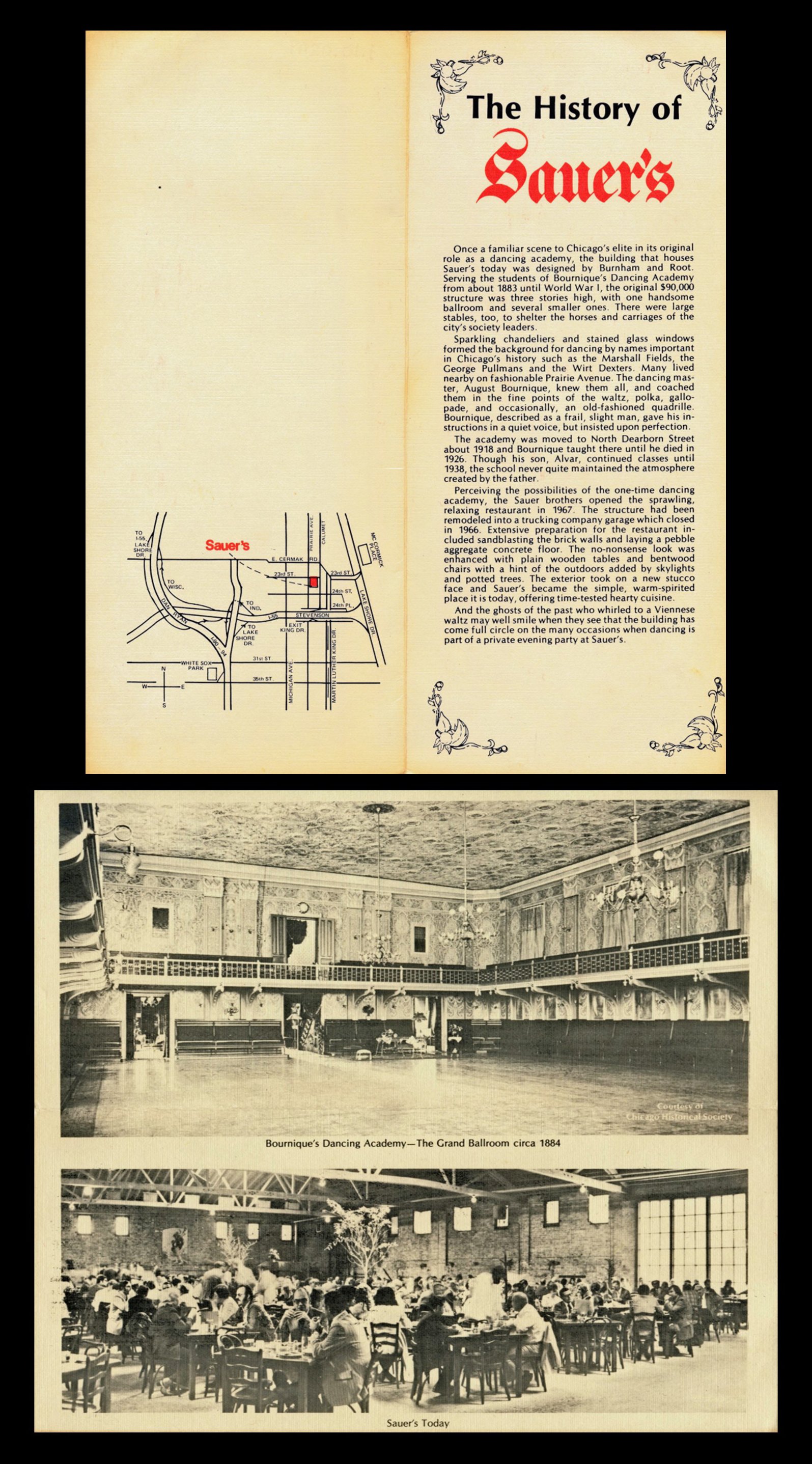

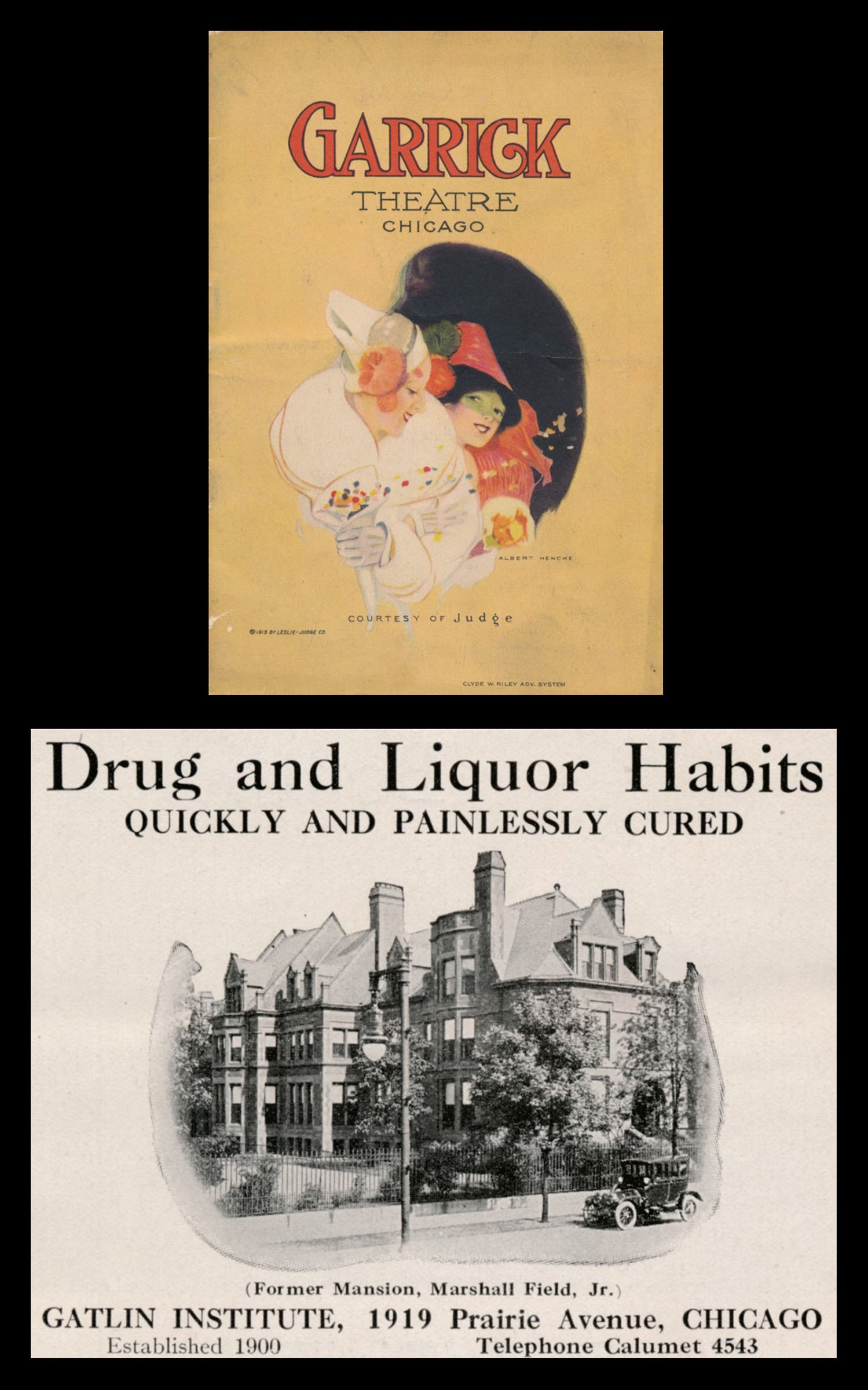

July 2023 - Brochure from Sauer’s Restaurant

The year 2023 marks the 140th anniversary of the opening of the exclusive Bournique’s Dancing Academy at 311 E. 23rd Street, as well as the 30th anniversary of the demolition of that building, following a period in which it housed Sauer’s Restaurant. The brochure above, recently donated to our archives, dates to about 1990 and was handed out to restaurant patrons who wished to learn more about the illustrious history of the building.

Augustus and Elizabeth Bournique opened their first Chicago dancing academy in 1867. After being burnt out of their State and Randolph location during the Great Fire of 1871, they opened academies on 24th Street and Madison Street. In 1883, they completed their elegant new building on 23rd Street east of Prairie Avenue, placing it immediately south of Chicago’s most exclusive residential district. Architects Burnham and Root designed the three-story Queen Anne style brick building which featured a dancing hall measuring 60 by 85 feet. A balcony above provided a “splendid observation point” and a music platform could accommodate 30 musicians. The decoration of the room included frescoes by S. S. Barry & Son, brass and copper combination gas and electric chandeliers by H. M. Wilmarth & Bro., leaded glass windows by W. H. Wells & Bro., and a remarkable parquet floor comprising 173,000 pieces, the whole bordered in ebony and cherry, provided by W. C. Runyon & Co. of Rochester, New York.

The children of Prairie Avenue all attended classes at Bournique’s, the ritual serving as a rite of passage, and leading to the introduction of many who later became husband and wife. The hall was also rented for large dinners and entertainments, which received extensive attention in the newspapers. Augustus Bournique retired in 1918, at which time his son Alvar took over the academy, relocating it to 1134 N. Dearborn Street. The move was an indicator of the change in the character of the neighborhood, the well-to-do families having abandoned their South Side lair for the North Side Gold Coast.

The Academy building on 23rd Street was stripped of its elegant appointments and converted into a trucking company garage which operated until 1966. The next year, the Sauer brothers opened their restaurant in the building. They sandblasted the exposed interior brick walls, installed a pebble aggregate concrete floor, added skylights between the roof trusses, and covered the front façade in white stucco. A 1970 review of the restaurant in the “Eating Out” column of the Chicago Tribune noted that popular fare ranged from a broiled hamburger on rye bread to a boiled brisket of corned beef with cabbage, each priced at $1.50.

In later years, the restaurant became equally known for its musical entertainment ranging from jazz to the emerging genre of house music, with frequent performances by Frankie Knuckles, today recognized as the “godfather of house music.”

The restaurant closed in 1993 and the contents and equipment were auctioned off, after which the building was demolished. Today, the site of the legendary building sits beneath a parking garage in the McCormick Place West Building.

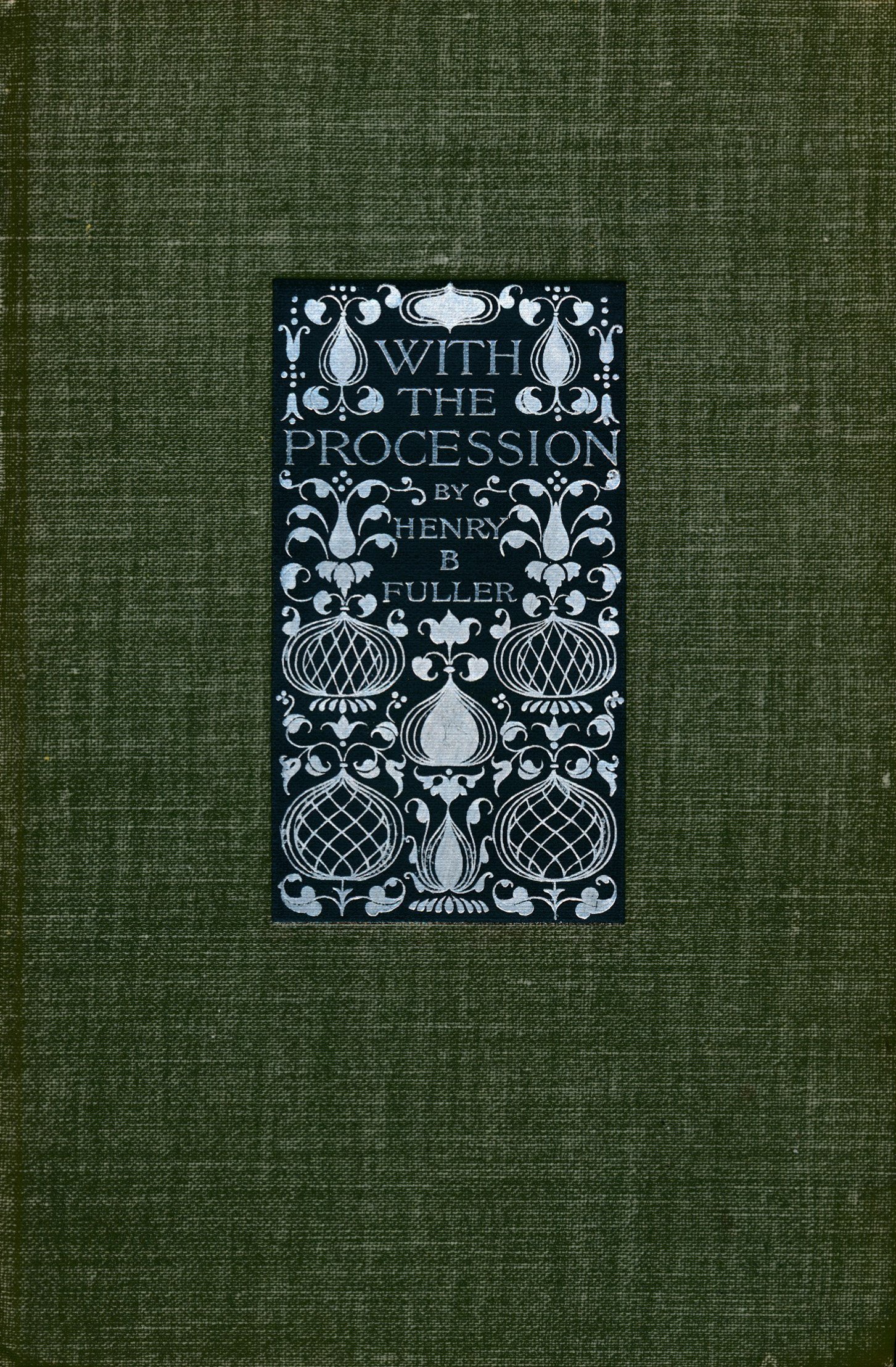

June 2023 - With the Procession by Henry Blake Fuller

In honor of Pride Month, we showcase Chicago author Henry Blake Fuller (1857-1929), and his 1895 novel With the Procession. The Glessners’ copy was recently returned to the library by a donor who found it in a bookshop. Fuller was important for several reasons, including his early exploration of homosexuality in fiction, for which he was posthumously inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in 2000.

Henry Blake Fuller was descended from Dr. Samuel Fuller (1580-1633), a passenger about the Mayflower and the first physician for the Plymouth Colony. Henry’s grandfather, Judge Henry Fuller (1805-1879), came to Chicago in 1849 and found his fortune constructing the Illinois Central Railway, laying the first water pipes in the city, and serving as superintendent of the Chicago City Railway.

As a young boy, Henry was described as a “solitary figure . . . quiet and delicate, preferring the company of his books to the boisterous games of boyhood.” His first published article appeared in the Chicago Tribune during his senior year in high school; he did not attend university.

Fuller’s first novels were styled as travel romances set in Italy. Critics drew similarities between Fuller’s writing and that of Henry James, and East Coast critics, including Charles Eliot Norton and James Russell Lowell, “took Fuller’s work as a promising sign of a burgeoning literary culture” in Chicago.

In 1893, Fuller published The Cliff-Dwellers, the first of several novels set in Chicago, the title being a reference to the skyscrapers redefining the city skyline at the time. It was well received by critics but was controversial among Chicago readers who found Fuller’s realistic portrayal of the industrial and multicultural nature of the city rather jarring. With the Procession was published in 1895 and was also based in Chicago. It follows the Marshall family, pioneers in Chicago, and their struggles to keep up “with the procession” of Chicago’s growth and industrialization. The tone of the novel was gentler than The Cliff-Dwellers and it was noted that his treatment of the Marshall family was inspired by his own family history as early settlers of Chicago. A review in The New York Times noted, in part:

“Sooner than we could have thought possible, a man has come to write the human comedy of the United States at the close of the nineteenth century, and we venture to assert that the particular impress of this man’s hand is likely to be a permanent one in American literature.”

In 1919, Fuller self-published Bertram Cope’s Year, after publishers passed on the novel, one of the very first to introduce homosexuality as a prominent theme. The story was set on the campus of Northwestern University. Highly satirical, it received poor reviews from the puzzled critics, and “embarrassed his friends.” It was not Fuller’s first work dealing with homosexuality. In 1896, he published a short play, At Saint Judas’s, about a gay man who commits suicide at the wedding of his former lover; it was the first American play to deal explicitly with the subject.

The Glessners were friends with Fuller, although how they were first introduced is unknown. In 1902, a note from Fuller reads “I shall be glad to take supper with you ‘most informally’ – my decided preference – next Sunday at half past six.” In 1907, John Glessner and Fuller were both charter members of the newly organized club, The Cliff Dwellers, which took its name from his 1893 novel.

Five of his works remain in the Glessner library today; in addition to With the Procession, they include The Chatelaine of La Trinité (1892), The Last Refuge: A Sicilian Romance (1900), Under the Skylights (1901), and On the Stairs (1918).

Fuller died of heart disease in July 1929 at the home of his long-time friend Wakeman T. Ryan in Hyde Park. His obituary noted that he was of “retiring nature” and refused to have his name listed in the telephone directory for fear of his retirement solitude being disrupted. He was interred in the family plot at Oak Woods Cemetery.

May 2023 - Ebonized slipper chair by Herter Brothers

Glessner House is fortunate to possess a set of three ebonized slipper chairs made by the great late-19th century furniture maker, Herter Brothers. Two of the chairs were returned to the house in 1968 by the Glessners’ granddaughter, Martha Lee Batchelder. The third chair, passed down through the son’s side of the family, was returned in August 2022. All were recently reupholstered, using a fabric very similar to the original gold silk damask, which is preserved on a back pillow in the archives.

Chairs such as these were produced by Herter Brothers starting in the mid-1870s, when the firm began to produce pieces influenced by Japanese design, featuring ebonized surfaces meant to imitate Japanese lacquerware. It is likely the Glessners purchased the chairs for their new Prairie Avenue into which they moved in 1887. By that time, Herter Brothers had established a store in Chicago, located in the Pullman Building at the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Adams Street. The Glessners made their first purchase from Herter Brothers as early as 1876, a letter from their New York office confirming the sale of an armchair covered in red moquette, for which the Glessners paid $90.00 (the equivalent of $2,550 in 2023 dollars).

The firm of Herter Brothers was organized in New York City in 1864 by German immigrant half-brothers Gustave and Christian Herter. It began as a furniture and upholstery shop but quickly expanded to provide complete interiors.

Prominent clients included J. Pierpont Morgan and William Henry Vanderbilt. During the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, the White House acquired several pieces including a slipper chair. The firm returned during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt to decorate the State Dining Room and the East Room, from designs by Charles Follen McKim. Chicago clients included the Union League Club, Cyrus McCormick, and George Pullman, who hired the firm to decorate the $100,000 palm house expansion of his Prairie Avenue mansion in 1892.

The firm closed in 1906. Christian’s son, Albert, started Herter Looms in 1909, to produce tapestries and textiles; it was basically the successor firm to Herter Brothers. The Glessners were good friends with Albert and his wife Adele.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted a major exhibition “Herter Brothers: Furniture and Interiors for a Gilded Age” in 1995. Their collection includes an ebonized slipper chair identical to those found at Glessner House.

The piece is known as a slipper chair due to its construction with a low seat that was two to three inches lower than a typical chair. The form was originally designed for the bedroom to make it easier for the heavily dressed and corseted woman of the late 19th century to be able to put on her shoes (slippers). It was an invention of the Victorian era and was designed in multiple styles ranging from Renaissance Revival to Eastlake. Our chairs, with their dark polished stain meant to imitate ebony, are a product of the Aesthetic Movement, popular in Britain and the United States from about 1875 to 1885, with its focus on the creation of art simply to be beautiful, best expressed in the mantra “art for art’s sake.”

Today, the set of three chairs with their beautiful new upholstery, add an artistic flair to the Glessners’ parlor, just as they did a century ago.

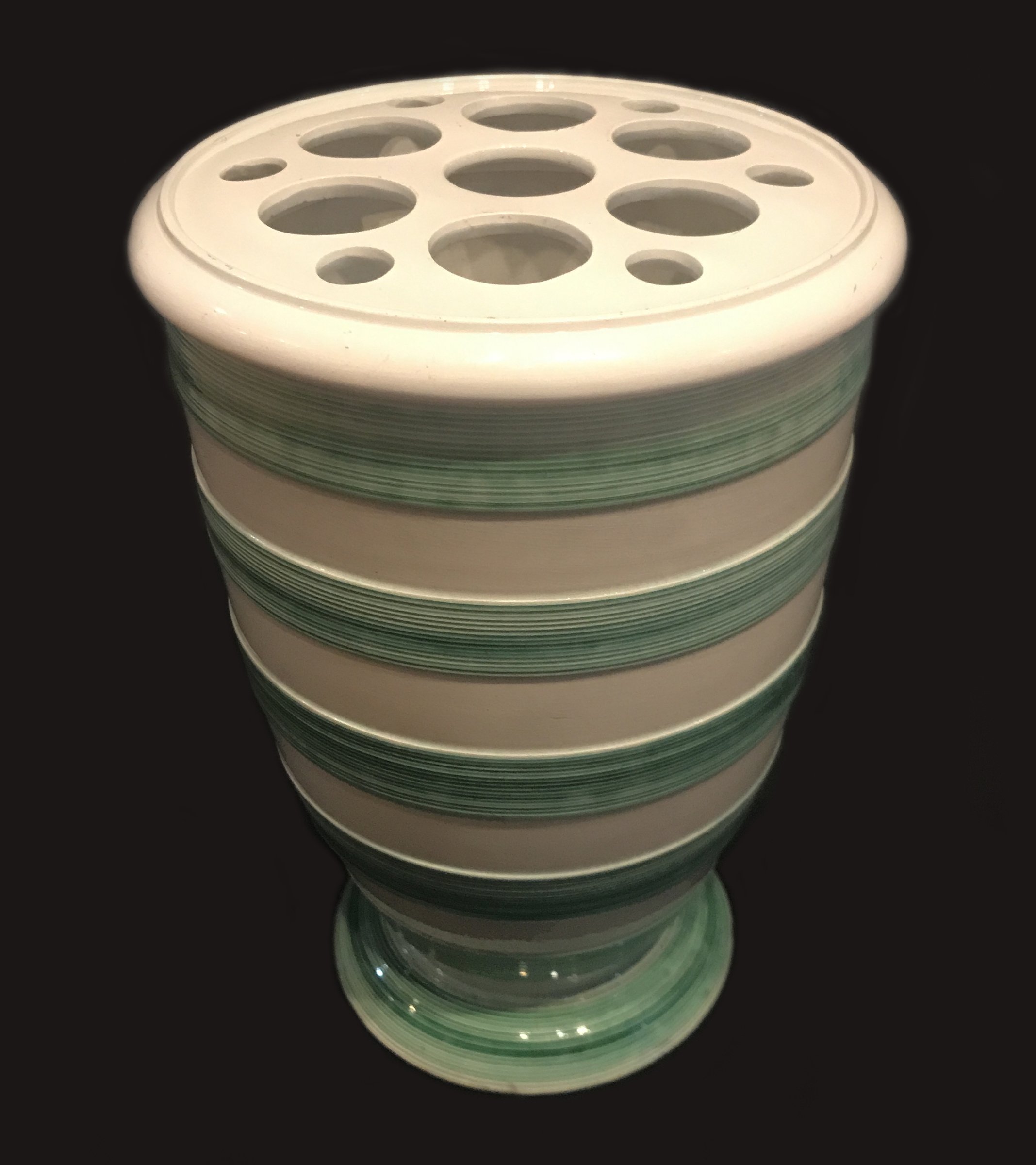

April 2023 - Wedgwood Bough Pot

This elegant earthenware vessel is an excellent example of a bough pot produced in England by Wedgwood in the latter half of the 19th century. The starkly modern design of the pot is reminiscent of other pieces acquired by Frances Glessner at the same time, showing her interest in simple line and form in lieu of elaborate decoration.

The firm of Wedgwood, long considered one of the premier manufacturers of English fine china, porcelain, and earthenware, was started in 1759 by Josiah Wedgwood. He had spent several years in partnership with Thomas Whieldon, the leading potter of the day, but was encouraged to start his own business after developing a new green glaze. Within a few years he developed his own version of creamware, a fine glazed earthenware with a creamy color that became known as “Queen’s Ware” after he presented Queen Charlotte with a creamware tea set for twelve. By 1780, Wedgwood had developed pearlware, which was whiter in appearance with a hint of blue.

He became best known for his unglazed stoneware, first produced in 1774, which he called Jasperware. The most common version featured a blue body with white relief work, the blue color coming to be known as Wedgwood blue. The firm remained in the Wedgwood family well into the 20th century and merged with Waterford Crystal in 1987; it is now part of the Finnish company Fiskars.

The bough pot, an example of pearlware, stands nine inches in height with the mouth measuring nearly six inches in diameter. It is topped with a removable pierced cover containing holes as large as 1-1/4 inches in diameter for holding branches and flowers. The only decoration on the pot is a series of horizontal bands highlighted in a vibrant green glaze, the color varying within the bands due to their ridged surface. It is interesting to note that pearlware pieces were only decorated in blue, yellow, and green as other colors could not withstand the heat necessary to fire the glaze on pearlware.

Bough pots became popular in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries to decorate interiors. They were often used to adorn fireplaces during the summer months, the large branches concealing the unused firebox. The pierced cover of the pot is also referred to as a flower frog – the term denoting a piece in which holes are used as guides for stems that could be inserted for arranging.

The pot is displayed on the west bookcase in the library in the same spot in which it can be seen in a 1923 image of the room. John Glessner specifically noted the piece in a paper he prepared for the Monday Morning Reading Class, indicating its prominence among the Glessners’ large collection of ceramics. The Glessners also owned the two volume set, The Life of Josiah Wedgwood by Eliza Meteyard, published in the 1860s and considered the definitive history of the man and his firm.

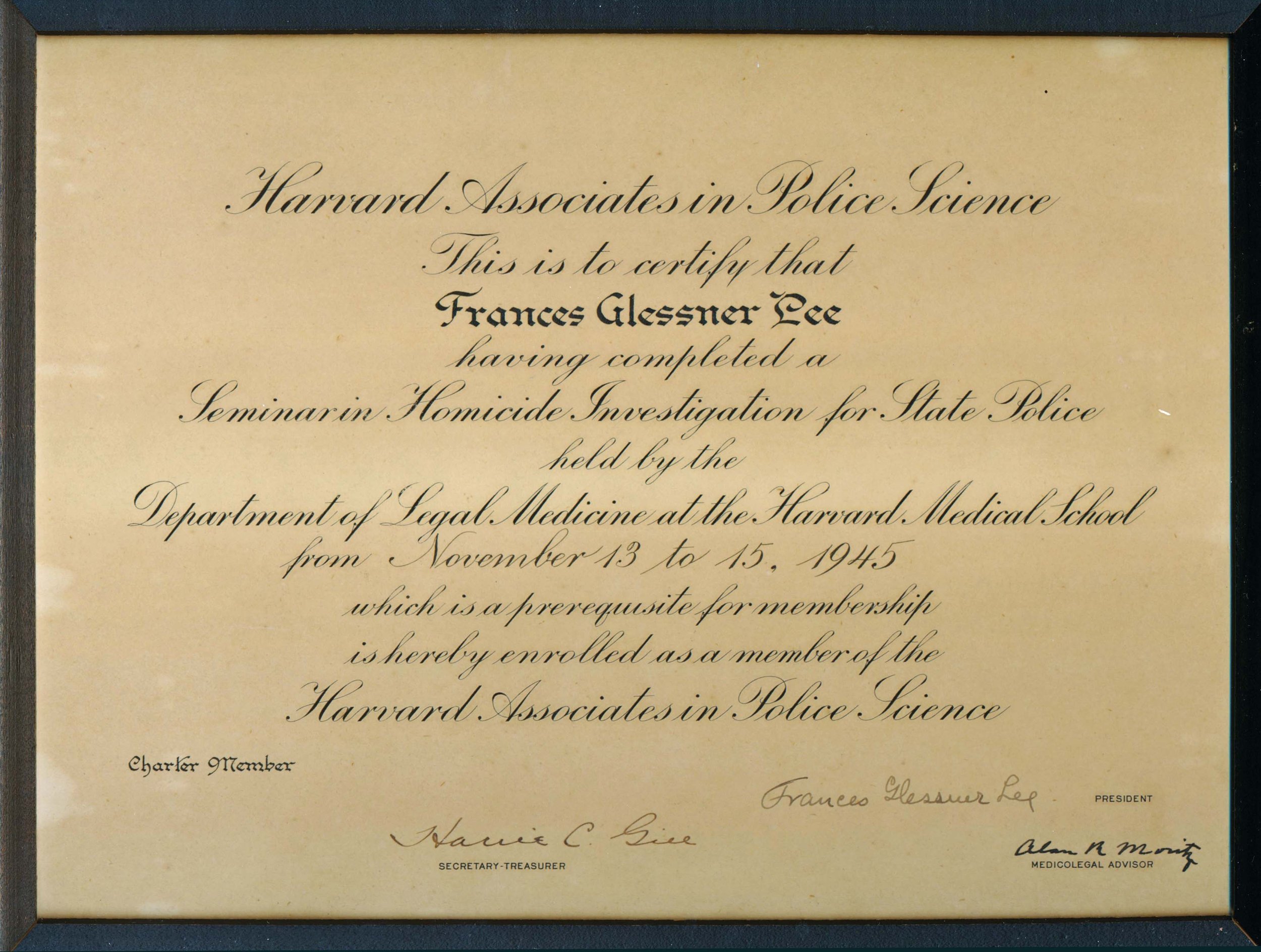

March 2023 - Harvard Associates in Police Science certificate awarded to Frances Glessner Lee

As part of Frances Glessner Lee’s work with the Department of Legal Medicine at the Harvard Medical School, she initiated biannual seminars in homicide investigation for state police. The first seminar took place in November 1945, bringing together state police officers from around the country, who had been nominated by their respective departments to attend the intensive training. Completion of the three day seminar conferred the status of “Harvard Associate in Police Science” upon the attendee. That designation could be used as a credential in a court of law. Additionally, the Associates would gather at conventions to continue their study of death scene investigation and would often confer on difficult cases.

Frances Glessner Lee not only organized the seminars, she also participated as an attendee at the first seminar, which she was able to do as a result of her having been appointed a Police Captain by the State of New Hampshire two years earlier. This participation resulted in her presenting herself with this certificate, which designates Lee as a charter member of the Associates. The certificate was signed by Lee, who served as President of the Associates, as well as Dr. Alan R. Moritz, chair of the Department of Legal Medicine. The third signature is that of Harrie C. Gill, who Lee appointed as the first Secretary-Treasurer of the Associates. Gill was an officer with the Rhode Island State Police and a nationally recognized expert on polygraph tests. During World War II, Gill used his skills to screen personnel for the Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear bomb.

The discovery of the framed certificate in April 2015 is an interesting story. The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests was in the process of purchasing Lee’s cottage at The Rocks. They asked Bill Tyre and John Waters of Glessner House to document the structure. During that process, Tyre and Waters stumbled upon a large suitcase in the attic of the cottage, bearing the initials F.G.L. Upon opening the suitcase, they discovered this framed certificate, along with several others designating Lee as a police captain in various states, plus other awards and documents relating to her years working with the Department of Legal Medicine. The suitcase and its contents were donated to Glessner House by the North Country Council, owners of the cottage at the time.

February 2023 - Zsolnay covered dish

This striking covered dish, which measures just 5-1/2 inches in height, is an excellent example of the work of the Zsolnay porcelain factory in Pécs, Hungary. It displays one of Zsolnay’s best known features – the beautiful iridescent finish, which is reminiscent of the work of English ceramicist William De Morgan, well represented at Glessner House.

The factory was established in 1853 by Miklós Zsolnay (1800-1880) to produce a variety of stoneware and ceramics. A decade later, his son Vilmos joined the company and led the efforts to make their wares known internationally, receiving awards at the World’s Fairs in Vienna (1873) and Paris (1878). During the 1880s, the firm began producing “pyrogranite,” a type of durable glazed ceramic that was used as roof tiles and outdoor decoration (click here to see the roof of the Post Office Palace in Pécs). Zsolnay was the largest company in Austro-Hungary by the early 1910s, but the World War, followed by Serbian occupation led to its decline. It recovered in the 1930s, but World War II saw the bombing of its factory, followed by Communist rule. It was not until 1982 that the company regained its independence. The firm still makes high quality pieces and the Zsolnay Museum in Pécs, located in the former Zsolnay home, displays many of its finest pieces.

The Glessners’ covered dish, which dates to the early 1900s, is in the form of a large egg set on end. The horizontal ribbing is an important part of the surface as the glaze, which appears to be iridescent metallic, changes colors with the angle of reflection. The main band of decoration comprises five pairs of cream-colored chickens surrounded by scrolling foliate work. Above and below, deep blue decorative motifs set against a silver stippled background cover the entire surface. The inside of the dish is covered in a luminous silver finish, similar to mercury glass. It is highly reflective and could easily be mistaken for metal. The base features the traditional Zsolnay mark which incorporates the towers from the Pécs Cathedral.

The iridescence is the result of a process known as eosin, introduced at Zsolnay in 1893. The term comes from the Greek word “eos” which refers to the light red color seen at dawn. Multiple eosin colors were developed over time, and they became popular with artisans during the Art Nouveau movement.

The covered dish is displayed on the mantel shelf in the corner guestroom. It is a reminder of the Glessners’ discriminating taste, and their appreciation for ceramics employing new and innovative techniques in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

January 2023 - Plaster model of Glessner House by the WPA

The 1930s was a time of significant recognition for Glessner House. The house was featured in two of the earliest architecture exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (1932 and 1936), and the related catalog for the latter, by Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Jr., was the first in-depth examination of architect Henry Hobson Richardson’s work in half a century.

This plaster model was created about 1939 by the Museum Extension Project (MEP) of the Pennsylvania Works Progress Administration (WPA). The goals of the MEP were two-fold. First, to produce visual materials for students across the state that would help them to better understand subjects ranging from architecture and design to maps and Native American crafts. Second, to provide employment to as many as 1,200 people at a time in its three divisions to produce the works, create children’s museums, and to assist in conservation work at museums around the state.

The plaster model of Glessner House was one of more than a hundred works of architecture that were each made to various scales. The house itself (exclusive of the base) measures approximately nine by twenty inches, indicating a scale of eight feet to one inch. Multiple copies would have been made of each model, and a school could order up to fifteen models at a time. The significance of Glessner House is confirmed by the fact that many of the models were of buildings in general – a Gothic country house or a modern town house – whereas Glessner House obviously depicts a specific building within the “Late American” category. The model would have been created from Richardson’s working plans, as evidenced by features shown that were later changed in the final design. The label reads, “Richardsonian Romanesque, 1885, Glessner House, Chicago.”

The model was acquired by Glessner House in 2007 and helps visitors understand the importance and recognition of the house nearly ninety years ago. Additionally, it affords an easy way to provide an aerial view of the all-important plan of the house and its site, and serves as a tangible reminder of the Great Depression and the enormous body of work produced by the WPA during that time.

For further information on the model and the MEP, read our blog article from March 2015.

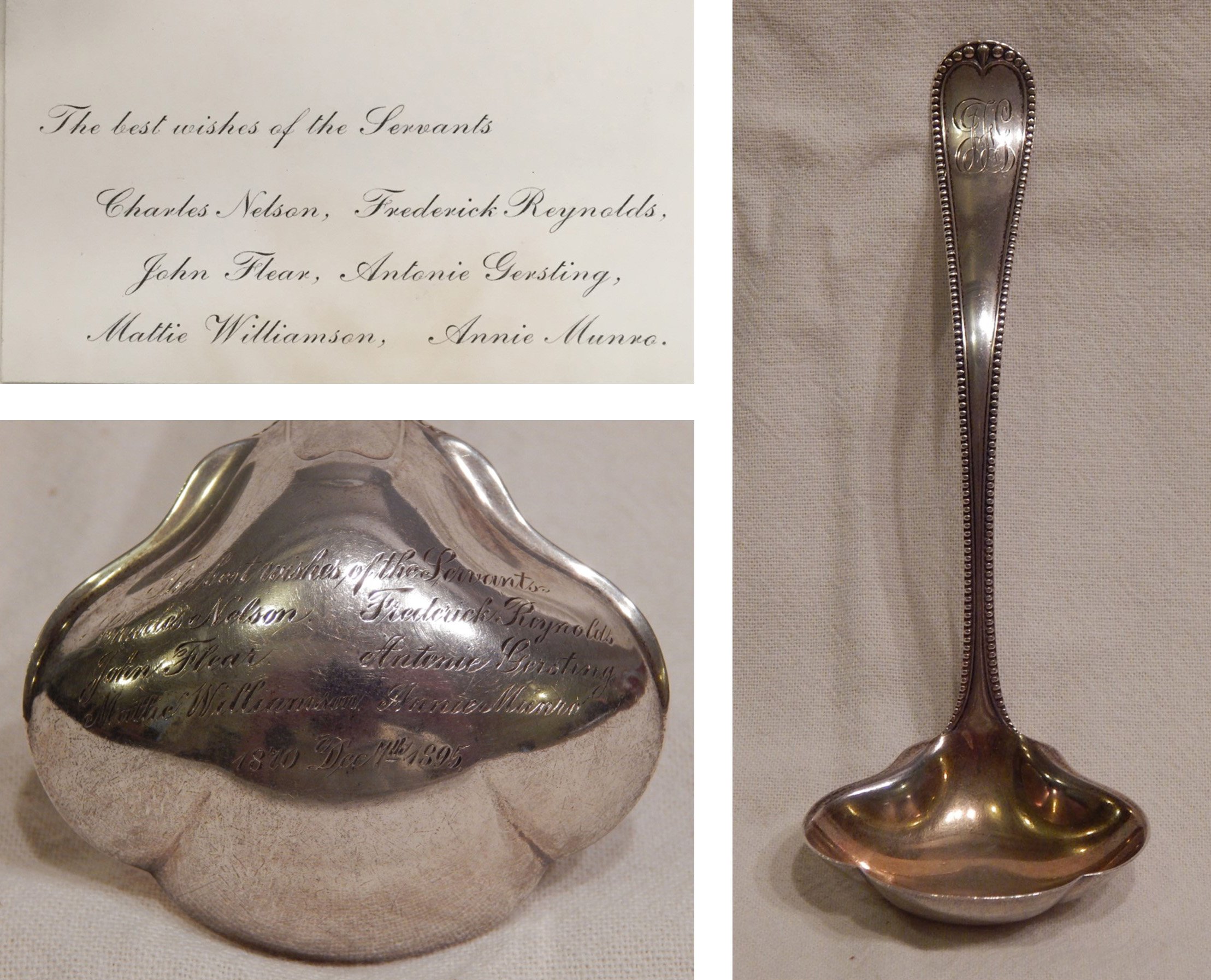

December 2022 - Sterling sauce ladle presented by the servants, 1895

On December 7, 1895, John and Frances Glessner celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary. Before heading to the symphony to hear a concert specifically programmed for them by music director Theodore Thomas, the Glessners and their two children enjoyed a quiet dinner at home. Frances Glessner recalled the following in her journal:

“At dinner I gave John a loving cup with twenty five bridesmaid roses in it. After a little while George brought me a beautiful silver water pitcher from him and Frances - then in a few minutes Frederick came and in a very graceful way asked me to accept two beautiful gravy ladles from the servants. With the spoons came a card “with the best wishes of the servants” followed by their names arranged according to the length of time they have been with us. These gifts were all in the most perfect taste and touched us deeply. After dinner, John called them in and thanked them for us both.”

One of the two sauce ladles (shown above) remains in the house collection. The sterling silver ladle was made by Gorham and retailed through Spaulding & Co. in Chicago. Gorham was one of the largest and most prominent American manufacturers of sterling and silverplate, and had been founded in Providence, Rhode Island in 1831. Henry A. Spaulding opened Spaulding & Co. in Chicago in 1889 after serving as the general representative in Europe for Tiffany & Co. for eighteen years. Located at the corner of State and Jackson, the store was a favorite of Frances Glessner.

The ladle, in the Newcastle pattern, features a long curving handle with the JFG monogram at top and delicate beading along the edge on both the front and back. The deep, scalloped bowl is gilt on the inside. What is most special about the piece, however, is the back of the bowl. Frances Glessner was so touched by the gift that she brought it to Spaulding & Co. and had the message from the card engraved on the back:

”The best wishes of the servants

Charles Nelson Frederick Reynolds

John Flear Antonie Gersting

Mattie Williamson Annie Munro”

To this, at the bottom, she added “1870 Dec 7th 1895” noting the dates of her wedding and her 25th anniversary.

Charles Nelson was the coachman and had been with the family since 1878. Frederick Reynolds joined the staff as butler in 1891. John Flear had served as footman for three years; in 1923 he returned as butler. Antonie Gersting was the ladies maid, Mattie Williamson was the cook, and Annie Munro was a maid; all had been with the family just a few years. Mattie would become one of the longest serving members of the household, remaining for twenty years until her marriage in 1912.

Frances Glessner’s thoughtful addition of the sentiment from the card (shown at upper left above) to the back of the ladle ensured that the story of its presentation to the Glessners on their anniversary would always be preserved.

November 2022 - Signed portrait of Frederick A. Stock

The Glessners received this large portrait of their good friend, Frederick A. Stock, as a Christmas gift in 1907. It is inscribed “To my best friends Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Glessner with all good wishes” followed by his distinctive signature, and a five measure musical quote to the left. The portrait was taken by Richard Gordon Matzene, Chicago’s premiere society photographer during the first decade of the 20th century.

The Glessners offered their friendship and unconditional support to Stock throughout his long tenure as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1905 until his death in 1942, the longest in the history of the orchestra. When Stock was officially appointed as music director, a few months after the death of Theodore Thomas, the Glessners hosted a dinner for the principals of the orchestra, during which John Glessner gave a toast that included these words:

”Now the Board has chosen a leader. Under him we hope to see our orchestra work grow better and better. I know he will do the best that is in him . . . I toast the rising star, Frederick Stock.”

On December 31, 1909, Stock premiered his first symphony, significant portions of which were composed during his stay with the Glessners at their summer estate, The Rocks, in New Hampshire. He dedicated the symphony to the Glessners, although the official program notes never mentioned them specifically by name. The dedication read, in part:

”This symphony was written in honor of two well-beloved people, man and woman, who have won for themselves the highest esteem and loyal friendship of many of the most worthy dwellers in the land . . . To these two people, whom the composer is privileged to number among his best and dearest friends, his symphony is most affectionately dedicated.”

The Glessners’ devoted support of their friend became especially meaningful in 1918, after the United States entered World War I. Stock had never completed his naturalization papers, and was therefore still a German citizen, in spite of having resided in Chicago since 1895. Anti-German sentiment was pressuring the Orchestral Association to remove Stock and other members who were German citizens. In July 1918, John Glessner wrote a letter to President Woodrow Wilson “expressing implicit confidence in (Stock’s) loyalty to the United States.” When Stock was forced to resign later that year, John Glessner expressed his desire to resign from the Board of Trustees, in order to stand with his friend. When Stock returned to the podium for his first concert after being reinstated in February 1919, he was celebrated that evening with a dinner at the Glessners’ home.

Frances Glessner died in October 1932, and Stock quickly inserted Bach’s Chorale-Prelude into the program. It was the first time the orchestra performed a piece in memory of a woman. When John Glessner died in January 1936, Stock programmed two pieces in his memory - Strauss’s tone poem, Death and Transfiguration for the Tuesday concert, and Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony at the regular Thursday evening concert.

The signed portrait serves as a tangible reminder of the precious friendship between Frederick Stock and the Glessners over a period of thirty years, manifested by countless dinners and entertainments that took place within the walls of 1800 South Prairie Avenue.

October 2022 - George Glessner’s pocket watch

This pocket watch was presented to George Glessner by his parents exactly 130 years ago, in honor of his 21st birthday. After his death in 1929, it was given to his son, John J. Glessner II, and it was passed down through his branch of the family, with George’s great-grandson, Oliver F. Wadsworth III, donating it to Glessner House in March 2022.

Frances Glessner recorded in her journal the celebration of George’s 21st birthday at their summer estate, The Rocks. Although his actual birthday was October 2, 1892, the family celebrated one week early, as George returned to Harvard a few days later.

“Today we are celebrating George’s coming of age. We had a beautiful gold watch (and chain) for him which Mr. Avery had made for him especially. Frederick and Mattie made him a lovely big cake which they ornamented. They had a little pyramid of pink and white in the middle and a little ladder on each side. Then Happy Birthday on it in red letters – 1871-1892 – J.G.M.G. We had twenty one candles burning.”

(Note: Frederick Reynolds was the butler and Mattie Williamson was the cook).

Mr. Avery was Thomas M. Avery, president of the Elgin National Watch Company. The Glessner and Avery families became close when they owned adjacent houses on Washington Street, the two properties taking up the full block on the north side between Sangamon and Morgan streets. Avery moved to 2123 S. Prairie Avenue in 1888, just months after the Glessners moved into their home at 1800.

The National Watch Company was organized in Chicago during the Civil War and completed its plant in Elgin, located west of Chicago, by 1867. The name Elgin became synonymous with the watches being produced there, so the company name was changed to the Elgin National Watch Company in 1874, around the time Avery was appointed president. Under his leadership, the company became the largest producer of watches in the world, producing about 500,000 per year by the late 1880s. He retired in 1899 and died two years later. The company survived until the 1960s at which time the plant was demolished.

The case of the watch is 18 karat gold and is inscribed “John George Macbeth Glessner, October 2, 1892” in elaborate script. The serial number, 3845058, indicates it was produced in 1889. It is a very high quality watch, so would have been made and then held for a discriminating buyer; thus the journal reference to Avery personally selecting it.

The movement is made of nickel, which became the premium in the late 1800s, replacing gilt movements in top-of-the-line watches. Nickel was more durable than gilded plates and offered a better surface for decorative machining and engraving. The movement of this watch displays damaskeening, a decorative patterning composed of very fine scratches made by a rose engine lathe using disks and polishing wheels. The fine patterns are similar to the results of Guilloché engraving.

The watch is open face, with the stem in the traditional 12:00 position, and the seconds bit, the small dial containing the second hand, at the 6:00 position. It features a convertible movement, meaning it could be modified so that the stem placement would be in the 3:00 position, which was typical for hunting watches.

We are pleased to have the watch back in the house for visitors to enjoy, after being cared for by four generations of the Glessner family. It is displayed in a dome on the mantel in George’s bedroom.

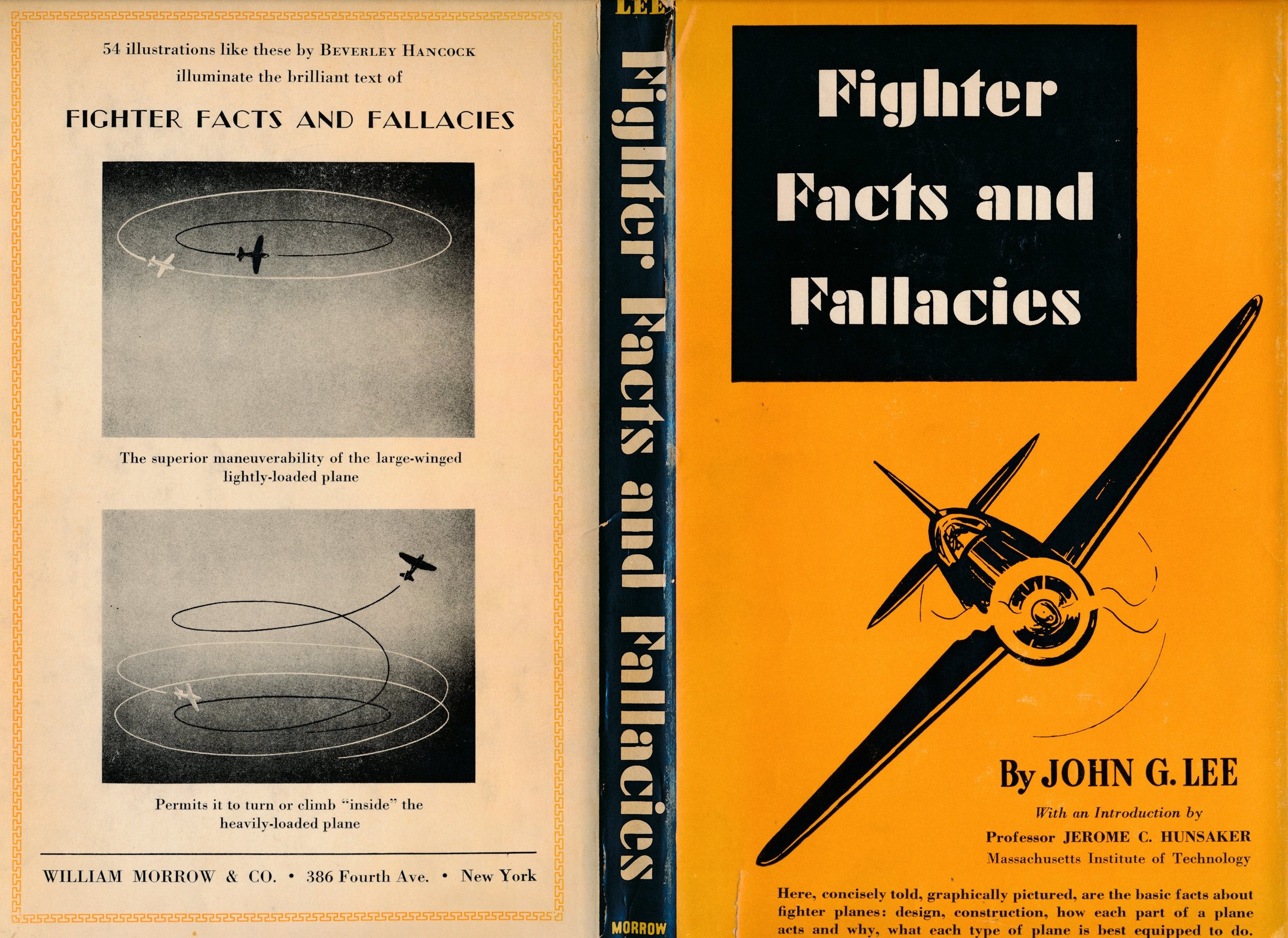

September 2022 - Fighter Facts and Fallacies by John Glessner Lee

In the fall of 1942, less than a year after the United States entered World War II, John Glessner Lee, the Glessners’ eldest grandson, authored Fighter Facts and Fallacies. It was published by William Morrow and Company and sold for $1.25. As noted on the dust jacket, the purpose was:

“to acquaint the general reader with the fundamentals of fighter design as the engineer sees them; to help him understand the problems facing both engineers and military men; and to provide for engineers, Army and Navy pilots and pre-flight students a concise, fully illustrated guide that tells the basic things they should know about their airplanes.”

The copy in the Glessner House collection is inscribed to his sister Martha with the postscript, “You don’t have to read it!”

Lee was born in Chicago in 1898 and received both his undergraduate and graduate degrees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the early 1920s. After teaching aeronautical engineering at MIT, he served as project engineer with the Ford Motor Co. where he helped design the Ford tri-motor plane. In 1932 he joined United Aircraft Corporation (later United Technologies and now Raytheon Technologies), where he was appointed assistant director of research in 1939 and research director in 1955. He retired from the company in 1964, later publishing It Should Fly Wednesday: Recollections of an Airplane Designer. He died in 1988.

The Introduction to the book was written by Jerome C. Hunsaker (1886-1984), one of America’s most distinguished aeronautical engineers and the founder of the aerodynamics curriculum and research program at MIT in 1914. In that same year, after working with Gustav Eiffel outside Paris, he designed the first wind tunnel in the U.S. (at MIT). By the time he wrote the Introduction in September, 1942, he was serving as Chairman of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). Of the book and its author, Hunsaker wrote:

“Fighter Facts and Fallacies by John Lee comes at a time when it is most needed. Many of us are confused and discouraged by statements of self-styled experts, in the press and over the radio, as to the relative merits of various German, Jap, or British fighters and our own. . . Mr. Lee’s discussion of the effects on performance of power, wing area, weight, and streamlining indicates how a designer thinks in juggling with his fundamental limitations. It also suggests what research men should be doing to lift some of these limitations. . . I am glad Mr. Lee has undertaken to explain in his clear and concise way the fundamentals of airplane performance. He is the most competent man I know to do this.”

After an explanatory preface, Lee divided his text into six chapters examining the effects of wing loading, power loading, weight increase, streamlining, span loading, and propellers. In the summary, he noted that “there is no ‘best’ fighter plane” and that circumstances will always determine the specific need. This is supported by two pages of clearly laid out factors affecting the performance of a typical fighter plane.

The text was accompanied by 54 illustrations created by Beverley Hancock (1903-1991), a talented commercial artist. Born in Chicago, Hancock received his degree in commercial illustration and design from the Pratt Institute in New York. He enjoyed a successful career as an advertising artist, occasionally been engaged by governmental agencies such as the U.S. Naval Observatory, for which he recorded the 1929 total eclipse of the sun. Hancock was a long time resident of Connecticut, and was a charter member of the Connecticut Association of Professional Artists when it was organized in 1948.

The book was reviewed in the December 1942 issue of U.S. Air Services, the reviewer, Esther H. Forbes, noting:

“In the midst of numerous contradictory opinions about the relative merits of American and foreign planes, a top-notch engineer has presented the average man with criteria by which he can judge the planes himself. In Fighter Facts and Fallacies John G. Lee, Assistant Director of Research at the United Aircraft Corporation, analyzes clearly and concisely – for airman and layman alike – the fundamentals of aerodynamics, the compromises which must be considered in fighter planes, and the problems of the designer in improving the performance of fighters.”

Forbes also noted the significance of Hancock’s illustrations:

“Perhaps the most intriguing feature of this book is the series of illustrations by Beverley Hancock. On page after page the author’s lucid text is dramatized in some of the most brilliant and original paintings and sketches to ever be published in the 39 years of heavier-than-air flight. Obviously author and artist have collaborated in complete harmony.”

Fighter Facts and Fallacies became a standard reference for professionals and the general public and was included in the first book list of the Technical Publications for Army Air Forces Field Technical Libraries, issued in December 1943. It is even included in the bibliography for the Wikipedia entry for “fighter aircraft.” Eighty years after its publication, it is a reminder of John Glessner Lee’s mastery of aeronautical engineering and his desire to provide essential information on fighter planes to U.S. citizens during World War II.

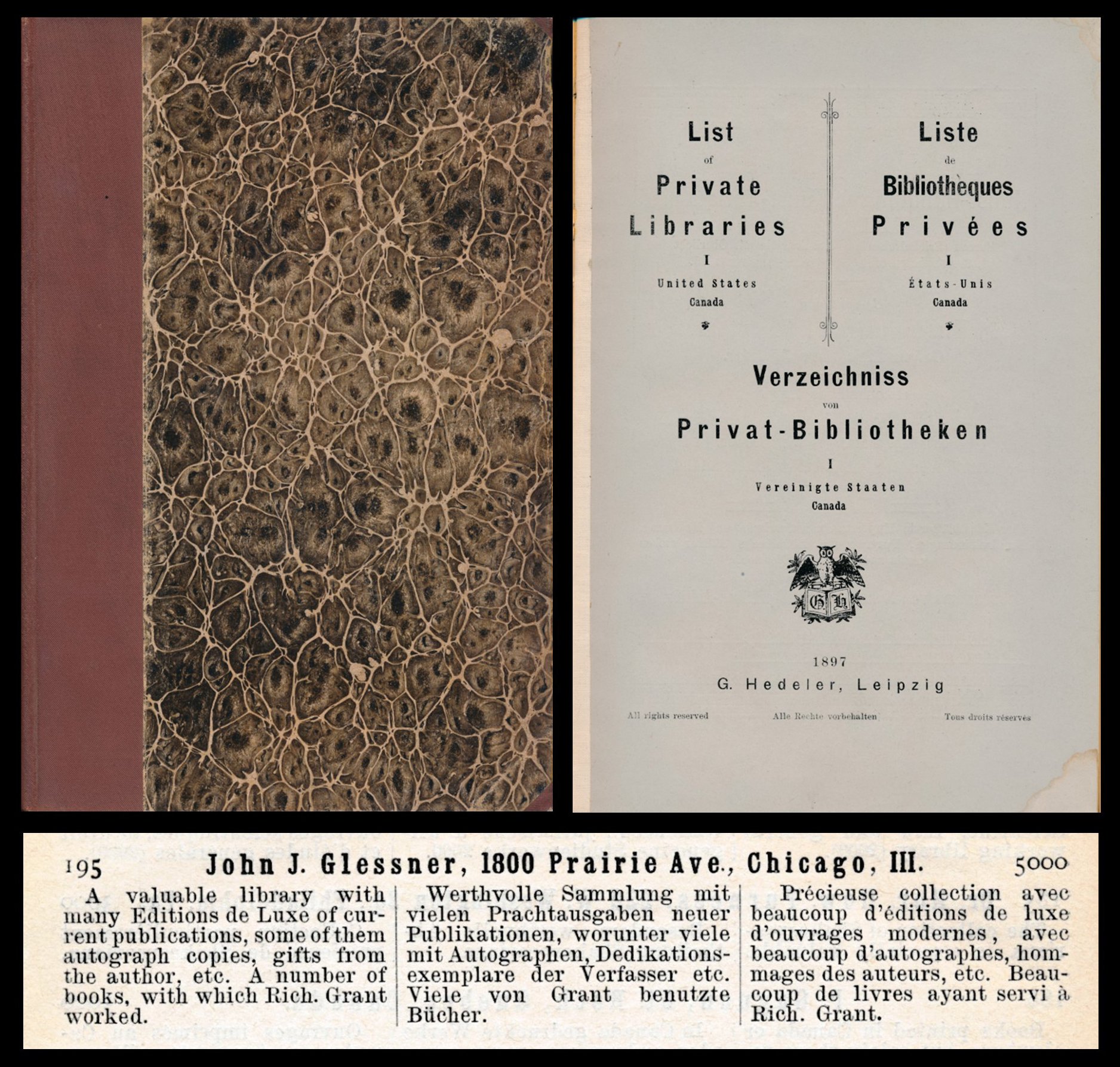

August 2022 - List of Private Libraries I: United States and Canada

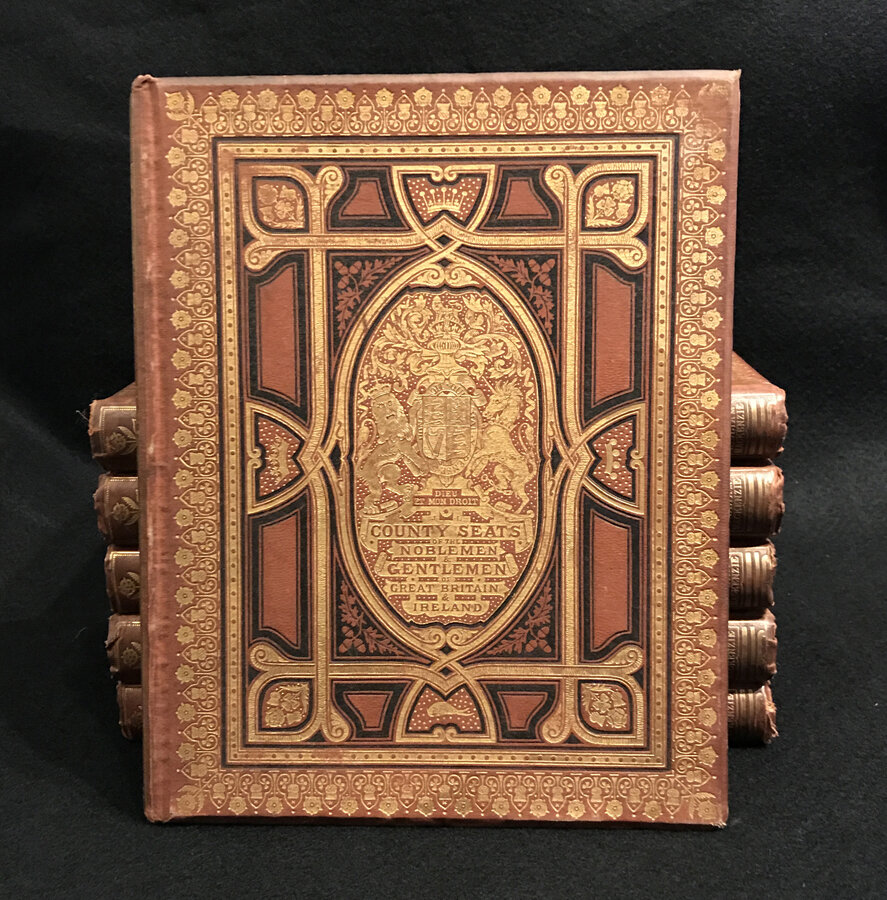

In 1897, exactly 125 years ago, George Hadeler of Leipzig, Germany published the first of three volumes enumerating significant private libraries. Volume I included libraries in the United States and Canada; later volumes focused on the United Kingdom and Germany. The book was printed in English, German, and French and featured a half binding of grained cloth and marbled paper. Somewhat unusual is the pagination, with every other leaf left blank. Numerous advertisements for European book dealers in the front and back of the book indicate the volume had a wide distribution there.

It is not known exactly how the listing was compiled, although one could assume the publisher worked with prominent book dealers to gather a list of clients. Additionally, one could submit information on their own library directly to Hadeler, as noted in this 1900 article about the publication of the second volume and a supplement to the first:

“Those possessors of libraries, with whom Mr. Hadeler has been unable to communicate, are requested to furnish him with details as to the extent and character of their libraries if they contain more than 3,000 volumes or have a special character. By doing so, they will, of course, not incur any expense or obligation.”

John Glessner was a serious book collector and his library of 5,000 volumes is included in Volume I, his entry reading:

“A valuable library with many Editions de Luxe of current publications, some of them autograph copies, gifts from the author, etc. A number of books, with which Rich. Grant worked.”

The library continued to grow, with Glessner’s 1936 estate inventory listing nearly 8,000 books in his libraries in Chicago and at his summer estate in New Hampshire. A number of books reflect his interest in book collecting, and a few, such as Private Libraries of Providence and Four Private Libraries of New York, show his specific interest in the contents of privately-owned libraries.

The reference in his listing to “Rich. Grant” is, in fact, a reference to Richard Grant White (1822-1885), one of the most important American literary critics of his day (and the father of architect Stanford White). In December 1885, Frances Glessner noted in her journal that they made visits to their favorite Chicago bookseller, Jansen, McClurg & Co., to inspect and purchase volumes from White’s library. White was an internationally recognized scholar on the work of William Shakespeare, so the Glessners would no doubt have been incredibly pleased with their purchase of White’s 21-volume set of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, published in 1821 (currently displayed in the second floor “Scott” bookcase).

A total of 44 Chicago libraries are listed in Volume I, including those of a number of the Glessners’ neighbors:

· Rt. Rev. Charles E. Cheney, 2409 Michigan Avenue (3,500 volumes, mostly historical works and theology)

· James W. Ellsworth, 1820 Michigan Avenue (5,000 volumes, including a copy of the Gutenberg Bible valued at $14,500)

· Edson Keith, Jr., 2110 Prairie Avenue (4,000 volumes, plus 125 manuscripts)

· Dr. Reuben Ludlam, 1823 Michigan Avenue (5,000 volumes, mostly medical)